The serpent Gurrangatch and the hunter Mirragan

28 June 2019This essay was presented by Bhante Sujato at a plenary session of the Sakyadhita 2019 conference in Leura, NSW. Global warming is an unprecedented threat to the survival of our civilization and culture, indeed our very lives. The aboriginal myth of Gurrangatch and Mirragan tells of a time when the land of the Blue Mountains was shaped in the struggle for life, a struggle marked by both passion and restraint. While the future has never been more uncertain, our wisdom traditions offer us ways of talking about and responding to change as conscious individuals able to reflect on and choose our own responses.

I want to bring something of my own land for you all today. The wisdom of our indigenous peoples has been disparaged or neglected, and the cost of that neglect is becoming ever clearer as our climate changes and nature is decimated. They looked after this land for 50,000 years, and we managed to stuff it up in a couple of hundred.

Around 1900 an ethnographer and surveyor named R.H. Mathews met with Gundungurra people of the Burragorang Valley and recorded the creation story of the serpent Gurrangatch and the hunter Mirragan; of how their struggle shaped the rivers, hills, and valleys we know today as the Blue Mountains.

I am not of the Gundungurra people, and this is not my story. Yet it is my land; not in the sense of ownership, but of belonging and kinship. I will never fully apprehend what it means to be one story with the land, to have my song be the land’s song. I experience the story of Gurrangatch and Mirragan not while walking the paths they forged in the tale, sheltering under the mountains they built, and drinking from the streams they swam, but via a constellation of interpreters and technologies, removed and abstracted. I cannot tell you what this story meant to the people who lived in this place. I can only say what it means to me, offering their story for you today in a spirit of the deepest respect for the Gundungurra people and their culture. This is a story of the dawn; let us see what it has to say to those of us who live in the twilight.

Follow the snakes from south to north to tell the story, and listen to Aunty Val Mulcahy, an indigenous storyteller, speak it in her own words.

Gurangatch vs Mirragang from Sean O'Brien Filmmaker on Vimeo.

Mythic echoes

As always with deep myth, we can tease out many threads from this story. It is a struggle between cosmic forces, an echo of the fires that shaped the land in geological time. Gurrangatch is an incarnation of the so-called “Rainbow Serpent” who figures in countless Aboriginal creation myths. The dragon or nāga mythology, so fundamental to Buddhist story and iconography, draws on the same set of mythic connotations, the formless powerful serpent hiding in the depths of the earth. The suttas speak of a serpent who glides along with fiery breath, manifesting a rainbow of colors (SN 3.1). At Wat Saman Rattanaram in Chachoengsao this has been brought to gloriously tacky life.

Source: https://amazing-bangkok.com/en/sightseeing/wat-saman-2/

In the curious mythological Vammika Sutta (MN 23), the protagonist must dig, dig, dig, and throw away all the odd things their digging reveals. At the bottom of all lies the nāga, but that is not to be thrown away: it is the enlightened one, and must be honored and revered. Here, the metaphorical road to enlightenment is not the ascent to higher spiritual realms, but the unearthing of the layers of the unconscious. The nāga symbolizes the deepest layer of all, that which is to be retained, not discarded.

Mirragan is the closest thing to a human protagonist in the story. He is a “tiger cat” or “quoll”, one of the many creatures that inhabit these woods that are neither kangaroos nor koalas. These days quolls are quite rare. Since the white man came, one species has become extinct and all that remain are in decline and under threat.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Spotted_Tail_Quoll_2011.jpg

As a mammal, the quoll is quick on his feet, resourceful. Mirragan’s technology and wiles—poison, spear, club—overmatch Gurrangatch’s primordial strength. He is passionate, proud, and capable, but his obsession brings danger to himself and his kin. Only his wife speaks words of moderation and wisdom. Heroes like Mirragan are remembered because they are so very rare. Far more common are those who get distracted along the way; or those who listen to the begging of the wife, and give up the heroic quest for a smaller, more domestic happiness. In this story, the wife plays the same role as Yasodhara; she is the normal life, the life of contentment for those of us who are not heroes. For every great myth that tells of leaving her behind, there are a thousand tales of the one who gave up the quest; for who could blame them?

But Mirragan’s true skill lies not in his persistence or his cunning, but in forging alliances; sending an unmistakable message of the importance of befriending others and maintaining relationships, it is only after he brings in the birds that he can win. Their attack on Gurrangatch, the birds of the air seeking out the chthonic monster of the deeps, recalls the universal mythic struggle of the phoenix or garuda versus the serpent or nāga.

Conscious incorporation

In all these motifs, and many more, there are points of interest, lessons to be learned, wisdom to be gleaned. But it is one little detail that strikes me most of all.

Just as the Vammika Sutta advises us to “leave the dragon”, the diver-bird fails to dislodge the monster. He contents himself with gouging off a piece of the serpent’s meat. This they consume, taking the serpent’s body into their own, becoming one in flesh. Mirragan, for all his destructive obsession with slaying the beast, is content with just this much.

In the Greek myths, Athena was a warrior maiden associated with the owl for wisdom and the olive for cultivation and civilisation. Her sacred olive has fruited in the Mediterranean region until the present, but even the goddess cannot stay climate change: Italy faces a 57% drop in olive harvest this year.[1] Athena was a thoroughly modern goddess, suitable for a cosmopolitan and sophisticated people. Among her many virtues, she aided heroes in their conquest of the dragon. Here, with an owl in her hand, she presides as Jason is released by the serpent who guarded the Golden Fleece.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Douris_cup_Jason_Vatican_16545.jpg

Yet on her breast she wore, not a symbol of the beauty and virtue with which she is associated, but something far more grotesque: the decapitated head of the serpentine deity Medusa, who turned men to stone with a glare. How she came by this gruesome relic is another story, but the point is this: the new cannot completely leave behind the old.

What does it mean to become one flesh with the monster? It is an acknowledgment that when we reform, we make progress in some ways, but we also unconsciously incorporate the echoes or the dark side of what has been reformed. We imagine that we are better, that we have surmounted and are pure: that is our temptation, our conceit, our precious.

How often have we seen reformers who, in no long time at all, become worse than the thing they replaced? In the political sphere it happens all the time. In reformist spiritual communities we can frequently see the resurrection of hierarchies, the imposition of judgmental rules and harsh standards, the assumption of ethical purity, the corruption of wealth, fame, and reputation, and the manipulation of doctrine to serve the interests of those in power. We must learn how dysfunctional behaviours work in spiritual communities, so we may leave them behind. We can only do that when we are equally conscious of the value of the past, of what is genuinely sacred in our traditions, so that we can preserve it and give it new life.

If we are just going to incorporate the flesh of the old in the new, replaying the old patterns out again, it is tempting to think that perhaps the chase is not worth it; maybe we should have listened to Mirragan’s wife after all. Psychologically, however, incorporating part of the old in the new is intrinsically healthy, an essential part of growth. Like any developmental process, it can go awry, for sure. But the new is not invented out of thin air. It must build on what came before. Incorporating the old is an act of compassion: it shows a connection between one and the other. It shows that, for all the limitations of the old, it was, after all, just a system built by humans who were trying to live. Yes, they made mistakes, and yes, we must do better. But we too are human and we will make our own mistakes.

I learned a key lesson on the nature of tradition from the aboriginal elder of the Nyoonga people, Ken Colbung. When I was only nineteen, I helped put together a seminar on vegetarianism. Hearing that Ken was vegetarian, I called him and asked if he would present with me, and he graciously agreed. He explained that in his traditional belief, animals were viewed as being brother or sister, so they would only be killed when it was absolutely necessary. A hunter would apologize to the beast, explaining that they needed to feed their family, and asking for forgiveness. These days, he said, there is no need to kill; he can just drive down to the market and buy some tofu!

This is what it means to have a living tradition. It is not a fossil preserved in stone, but something organic and evolving; we reflect on it, consider it, discuss it, improve it. We are aware of the ways in which we are shaped by the past, for good and for bad, and we try to do better. But awareness—real, clear-eyed awareness—takes guts.

Deep adaptation

With awareness and reflection comes choice. We do not have to be driven by the agendas of the past, for their struggle is not our struggle. We face new challenges, and for us, the greatest challenge is global warming. If our morality is the morality of the past, if our consciousness is the consciousness of the past, we choose to make ourselves unfit for the future. Reforming Buddhism is great; creating conscious spiritual communities is great; improving gender equity is great: but none of it means anything if our entire ecosystem is headed for collapse. In the face of the imminent existential threat of climate catastrophe, all our moral priorities and agendas must be urgently reconsidered.

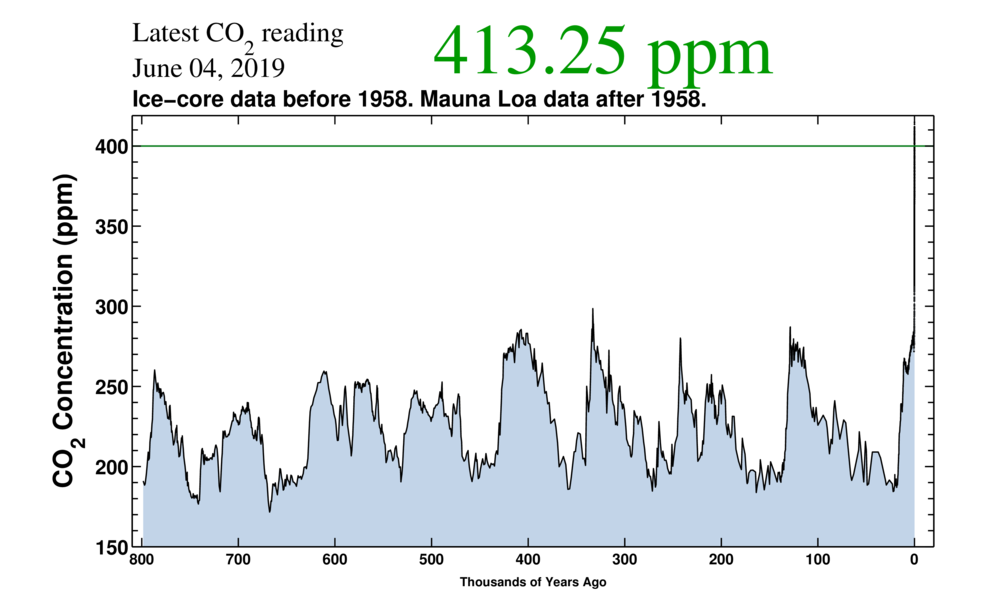

Source: https://static.skepticalscience.com/graphics/CO2_history_1024.jpg

Global warming is all around us and all through us. We incorporate the flesh of change in the air that we breath, in the water we drink, it is in our own flesh and bones. Look around you, see the mighty, endless forests, that have lasted from the days of Mirragan and Gurrangatch. Australia has, still, one of the fastest rates of forest clearance anywhere in the world. This state, New South Wales, is one of the world’s greatest coal-producing regions; and it is no coincidence that the level of renewables in our electricity production is stuck at a miserable 13%. Our politicians, incredibly, tell us that “now” is the time for government to push the creation of new coal power plants,[2] while fish die off in their millions, and still we don’t even have a target for renewables.[3] When you turn on the lights, you are killing those trees. They are dying because of how we are living. The canopies are thinning, the seeds are reducing, fire is increasing, and their ability to recover is collapsing; so much so that even sober scientists say “the whole thing is unraveling”.[4] Species are becoming extinct before we even know they exist; Australia is losing its frogs, which are especially vulnerable to changes in water supply and temperature.[5] As Australia suffers through yet another year of record-breaking temperatures, drought, fire, heat, and all manner of more obscure changes are creating a hidden, invisible crisis to countless little creatures of the forest,[6] like the possums who are simply dropping dead from the trees from heat stress.[7] It is not just on the land; in fact the vast majority of all the extra heat on earth is in the oceans, which now suffer from “heat waves” that devastate forests of kelp and cities of coral.[8] And as I write, the indigenous people of the Solomons face a black tide of dead fish, unable to swim or to eat as their waters have been poisoned by an oil spill.[9] Meanwhile, the mining conglomerate Glencore has been busted sponsoring covert operations to spread lies about coal,[10] and a deal has been signed for two massive new coal power stations, just down the road from here in the Hunter Valley.[11] How do they justify all this? Listen to the argument of Kepco, the South Korean firm that wants to open a new coal mine in the Bylong Valley, not far north of Joolundoo where Mirragan caught Gurrangatch. When the courts stopped their development because of climate change impact, their response was: our project will make a negligible contribution to global warming. In the scheme of things, what’s an extra 200 million tonnes of CO2?[12]

One of the nice things about writing on global warming is that research is super-easy. The articles I referenced in the previous paragraph were chosen by a simple criteria: they appeared in the news during the three or four days it took me to write this piece. That’s right: these stories on global warming were all published between the 4th and the 7th of March this year. Between then and now there will have been hundreds more like them. This is the rate of change we face, and the depth of the challenge.

The last form of denial is the denial of the activist: the idea that by continuing to do the same things we have been doing for a generation, this time it will make the difference. We sign our petitions, choose our organic veggies, prefer renewable power. Meanwhile, the CO2 in the atmosphere keeps going up, and the temperatures keep rising.

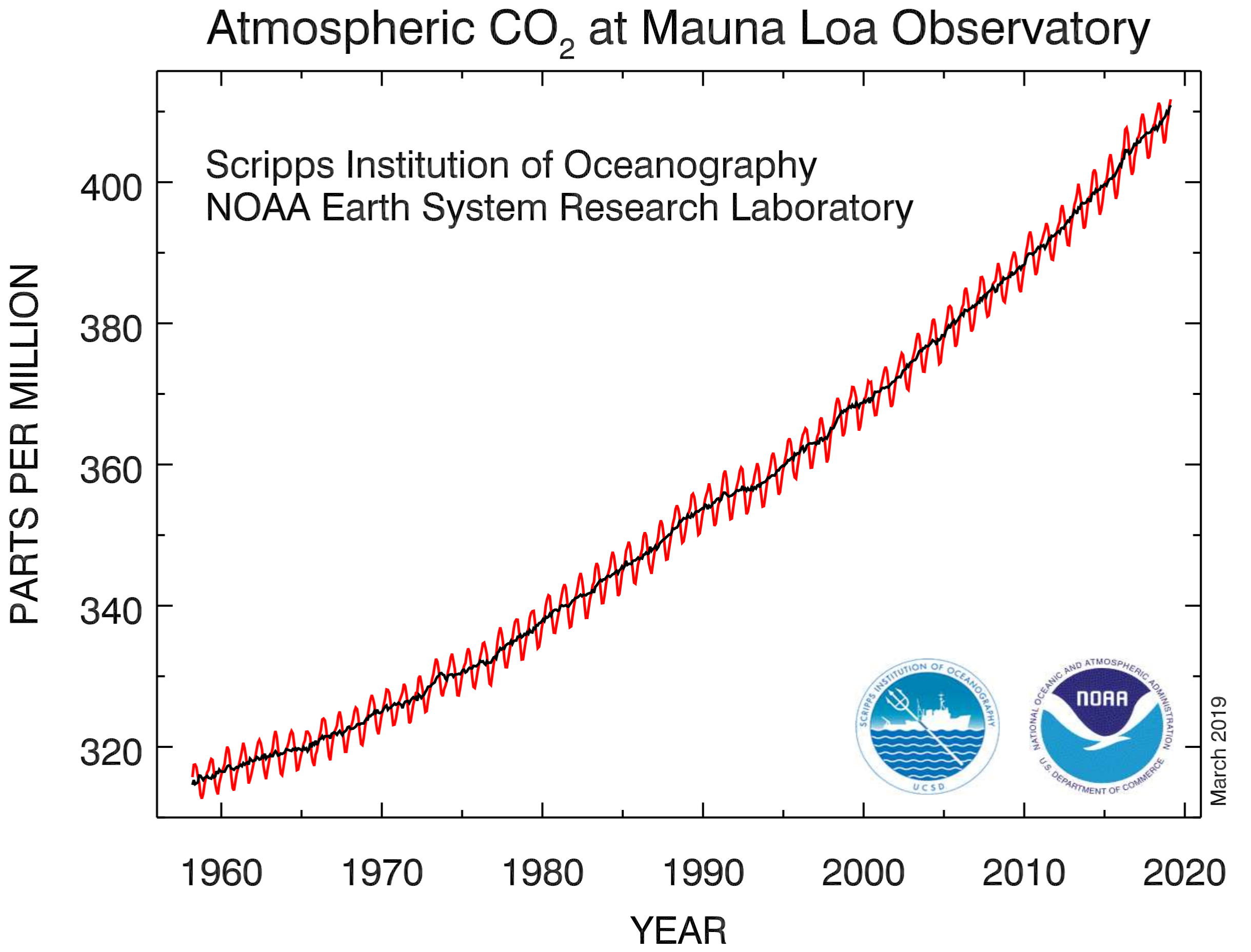

Source: https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/webdata/ccgg/trends/co2_data_mlo.pdf

This can be considered as a graph of the rise in global atmospheric CO2 since the post-war acceleration of industrialization. Alternatively, it could be considered as a graph of the rise in global atmospheric CO2 since the beginning of the modern environmental movement. How can this be? It is because the kinds of things that we do to prevent climate change are already factored in. They are business as usual. And the net result of all this effort is the world we are living in right now. If we continue to do the same kinds of things, we will continue to fail.

Painting a compelling, detailed picture of the climate collapse that is looming in the coming decades, Professor Jem Bendell speaks rather of “deep adaptation”.[13] It is a questioning of the fundamental values and course of our lives, facing honestly the emotional and spiritual stress of living in a world that is coming to an end, and asking what life might be like after the collapse.

Bendell discusses at some length the emotional ramifications of facing up to climate catastrophe. We feel scared, confused, let down, even risking plunging into despair and depression. Yet he points out that despair is not universally seen as a bad thing. The great spiritual traditions, including Buddhism, acknowledge that despair can be a spur to deep introspection and transformation. Think of the crisis that Siddhattha went through when he faced up to the reality of universal death and suffering. There is a way out, but we will not find it through denial or mollycoddling.

What then might we, drawing upon the best of our Buddhist traditions, have to offer the world in this time of unprecedented crisis? We must start by speaking the truth; and just this much is already a great deal. Too many of us harbor our worries and fears in secret, unable to speak them because, well, when is the right time to talk about the end of the world? Far from bringing despair to people, many are already facing a quiet despair. Even little children view the future through the lens of apocalypse rather than utopia. Our Teacher has taught us that all things are impermanent, that we should not hide from change, but should live each day in awareness and compassion.

Source: https://www.dw.com/en/this-apocalyptic-is-how-kids-are-imagining-our-climate-future/a-40847610

Perhaps the most powerful thing we have to offer is renunciation. The joy of simplicity and contentment. The knowledge, learned from our own experience, that with a simple life comes clarity and ease. Enough, as Mirragan eventually came to learn, is enough. Too often renunciation is seen as a purely monastic virtue, when it is there for everyone in Right Thought of the Noble Eightfold Path. It will not be long before renunciation is no longer a choice. Our children will have less than we, and their children less still. Having less, consuming less, is the most powerful way we can minimize the damage that we do, while also preparing ourselves to cope with the changes that we cannot prevent.

Finally, I would point out once more the key to Mirragan’s success: he worked with his friends. The Buddha said that good friendship is the whole of the spiritual path, and creation of meaningful intentional communities (Sangha) has always been a core aspect of his dispensation, and through the Sangha, the Dhamma has survived for 2,500 years. In the days to come, those who survive will not be the preppers or the survivalists in their bunkers, or the billionares with their walled estates and private armies. It will be the villagers and the tribespeople. Those who know how to work together, to create local, small-scale systems of work and exchange, who understand and respect the land and the sky and the water, the beasts and the plants. These are skills still found in Buddhist villages across Asia—perhaps we should start learning from them.

Mirragan pursued his goal, ferociously and relentlessly. But he was content to eat just a piece of flesh, leaving the great serpent-spirit alive and safe in the depths. That is why they both survived, a living presence in the landscape to this very day. We have shown no such restraint, no such wisdom. We kill the serpent, poison his waters, and wipe out his forests.

I don’t come here to bring you hope. It’s too late for that. We don’t need hope; what we need is courage. Stay close to each other, support each other, live simply in the real world, and listen to the truth whispered to you in the trees. Never be afraid to step forward and show leadership to share your wisdom and compassion. As spiritual practitioners, it is up to us to show honesty and realism, to set an example of how it is possible to live in the face of radical change. Impermanence is core to our philosophy: are ready to live it? This world, this beautiful fragile world, needs you more than you know.

Sources for the story of Gurrangatch and Mirragan

- “Gurangatch vs Mirragang.” Oral record by Aunty Val Mulcahy. Published on the ABC “Mother Tongue”, Sean O'Brien, producer, 29 January 2015.

https://open.abc.net.au/explore/86834 - “Some Myths and Legends of the Australian Aborigines.” W.J. Thomas. First published in 1923.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/aus/mla/mla18.htm

Footnotes

“Italy sees 57% drop in olive harvest as result of climate change, scientist says.” Arthur Neslen, The Guardian, 5 March 2019.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/mar/05/italy-may-depend-on-olive-imports-from-april-scientist-says ↩“‘Now’ is the time for new coal plants, resources minister says.” Katharine Murphy, The Guardian, 7 March 2019.

https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/mar/07/now-is-the-time-for-new-coal-plants-resources-minister-says ↩“NSW election: Nationals’ hold on environment policy drags down Coalition.” Anne Davies, the Guardian, 7 March 2019.

https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/mar/07/koalas-and-climate-to-the-fore-as-environment-looms-large-in-nsw-election ↩“‘Whole thing is unraveling’: climate change reshaping Australia’s forests.” Graham Readfearn, The Guardian, 7 March 2019.

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/mar/07/whole-thing-is-unraveling-climate-change-reshaping-australias-forests ↩“Climate change puts additional pressure on vulnerable frogs.” Graham Readfearn, The Guardian, 6 March 2019.

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/mar/06/climate-change-puts-additional-pressure-on-vulnerable-frogs ↩“Out of sight, out of luck: the hidden victims of Australia’s deadly heatwaves.” Graham Readfearn, The Guardian, 4 March 2019.

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/mar/04/out-of-sight-out-of-luck-the-hidden-victims-of-australias-deadly-heatwaves ↩“‘Falling out of trees’: dozens of dead possums blamed on extreme heat stress.” Lisa Cox, The Guardian, 7 March 2019.

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/mar/07/falling-out-of-trees-dozens-of-dead-possums-blamed-on-extreme-heat-stress ↩“Australia’s marine heatwaves provide a glimpse of the new ecological order.” Joanna Khan, The Guardian, 5 March 2019.

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/mar/05/australias-marine-heatwaves-provide-a-glimpse-of-the-new-ecological-order ↩“‘We cannot swim, we cannot eat’: Solomon Islands struggle with nation’s worst oil spill.” Eddie Osifelo and Lisa Martin, The Guardian, 6 March 2019.

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/mar/06/solomon-islanders-suffer-worst-oil-spill-nations-history-bulk-carrier-bauxite ↩“Revealed: Glencore bankrolled covert campaign to prop up coal.” Christopher Knaus, The Guardian, 7 March 2019.

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/mar/07/revealed-glencore-bankrolled-covert-campaign-to-prop-up-coal ↩“Deal signed for huge coal-fired power plants in Hunter Valley, Hong Kong firm says.” Ben Smee, The Guardian, 6 March 2019.

https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2019/mar/06/deal-huge-coal-fired-power-plant-hunter-hong-kong ↩“Korean company planning Bylong Valley mine dismisses climate threat.” Lisa Cox, The Guardian, 6 March 2019.

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/mar/06/korean-company-planning-bylong-valley-mine-dismisses-climate-threat ↩“Deep Adaptation: A Map for Navigating Climate Tragedy.” Jem Bendell, 26 July 2019.

https://jembendell.wordpress.com/2018/07/26/the-study-on-collapse-they-thought-you-should-not-read-yet/ ↩