Harbingers—I’d rather be a Doomer than a Boomer

22 September 2020“Harbingers” is an ongoing series of articles, stories, and reflections by Bhante Sujato on living in the age of global warming.

My news source of choice, The Guardian, recently published an article by Alexandra Villarreal on the so-called climate “doomers”: Meet the doomers: why some young US voters have given up hope on climate . I have previously critiqued their coverage of climate change, and will repeat here the caveat that I made there: I do this out of love. The Guardian is the best mainstream source on climate change and other issues, and their work is invaluable. But that doesn’t mean they’re perfect.

The premise of the article is true and important. There are young people in the US (and elsewhere) who are really convinced that the end is certain. And this has genuine implications in terms of mental health and political engagement. But this article, to my mind, exemplifies all the wrong ways to address this.

The essence of the critique of “doomerism” is that it prompts people to despair. This is a false dichotomy, stemming from the Christian value of “hope”, which in turn derives from Christianity’s origins as an apocalyptic cult who believed that Jesus would return in their lifetimes, and had to deal with what happened when he failed to show up. “Hope” was changed from being a realistic expectation of a positive outcome to being a metaphysical absolute. The righteous must clung to it despite all evidence, for the relinquishment of hope is a sure sign of spiritual and moral depravity.

But hope is not a value in Buddhism, and so the opposite of hope is not despair. To motivate our goodness, we look to the present, to what we can see. And when we do turn to the future, we keep our expectations grounded in what is reasonable and based in evidence. Rather than insisting on hope at all costs, we should ask ourselves, is something worth doing because it is good? If it can help ourselves or others, even a little, it is still worth doing.

Climate scientist Michael Mann is quoted in the article. He is a legend, and I have nothing but respect for his work on climate change. But I fear that his response to doomerism misunderstands the spirit of the times; against doomerism he posits boomerism.

He thinks that existing institutions can be influenced and tweaked to work in favor of the environment. The problem is, people like him have been trying to do that for decades, and it hasn’t worked. How long can you keep on saying, “Just a bit more, let’s do the same thing again, this time it’ll make a difference”? At what point does this ring hollow?

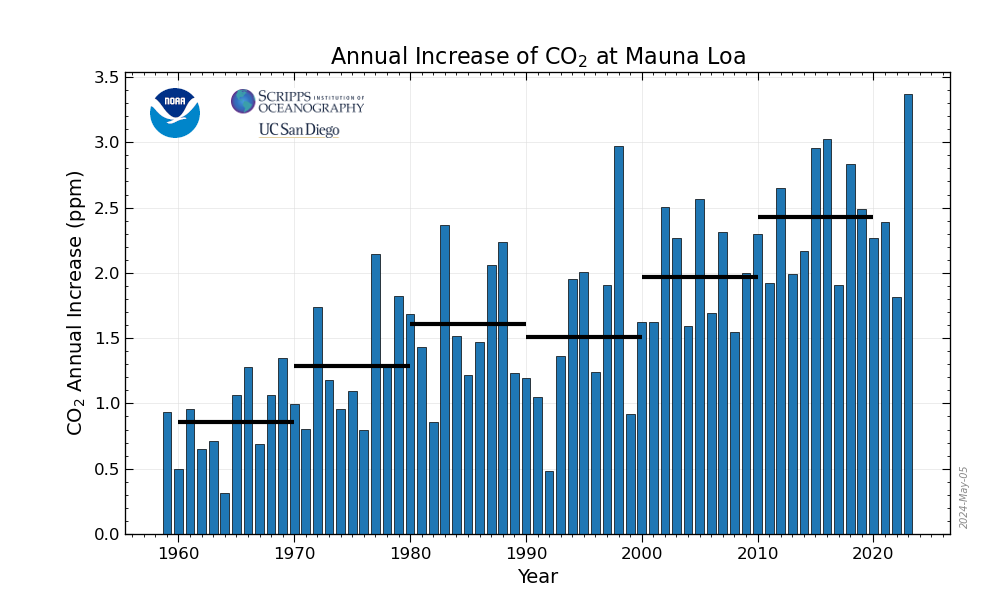

Mann points to Russian disinformation and scientific misunderstandings as the source of doomerism. Me, I’m more convinced by the fact that CO2 levels just keep going up. This is not caused by the conventional environmental movement, but it sure hasn’t been stopped by them.

Atmospheric CO2 is not just growing, it is doing so at an accelerating rate:

Cut young people some slack. It isn’t their fault that we are in this situation: it’s ours. And it isn’t their fault that the enviornmental movement has utterly failed to reduce atmospheric CO2: it’s ours.

I’m concerned about the shallow argumentation and lack of supporting evidence in this article, which I fear reflects a shallow understanding of the problem at large. If you follow the links, for example, they are of surprisingly poor quality. Under “false equivalency between Trump and Biden”, for example, we find a blank page.

Under “discouraging climate activists” one might have hoped to find some information about empirical studies on the effectiveness of different rhetorical strategies. Instead, we find a tweet(!) The tweet, by Alexandria Villaseñor, reads:

Greta sparked a movement that has thousands of youth learning about climate change and realizing they have power. what have you done @RoyScranton? besides tell us we’re doomed so we should go back to school and learn how to be good little capitalists.

This is evidently in response to Scranton’s remark in the linked article. I will leave it to the reader to follow up on this and see whether it is an accurate representation of Scranton’s position.

But what is curious to me is the description of Greta Thunberg’s success. Let me be clear: I think Greta Thunberg is one of the most amazing human beings in existence. Hear her words at the 2019 United Nations Climate Action Summit:

You have stolen my dreams and my childhood with your empty words. And yet I’m one of the lucky ones. People are suffering. People are dying. Entire ecosystems are collapsing. We are in the beginning of a mass extinction, and all you can talk about is money and fairy tales of eternal economic growth. How dare you!

She is incredible. But what, exactly, has she achieved? If the point of the tweet was to contrast Greta’s success with Scranton’s failings, what does that success consist in? Convincing young people they have power? Power to do what, exactly? The only power that actually matters is the power to reduce atmospheric CO2. Until they do that, climate change remains on full steam ahead.

To avoid misunderstandings, I agree completely with everything Greta has inspired. If anything, I don’t think it goes far enough. I think all schoolchildren everywhere in the world should simply refuse to go to school until the climate crisis is solved. Maybe that would get some action. Until then, as Greta herself has said, all her school strikes and her activism have, in her words, achieved nothing.

Another link appears for the text, “the Chinese economy [has made] substantial progress diversifying from coal”. This links to a puff piece published by a “bipartisan” US think tank whose board members include Henry Kissinger, Zbigniew Brzezinski, former heads of US DoD and CIA, and CEOs of Boeing, Coca-Cola, Hyatt Hotels, various banks; oh, and Rex W. Tillerson, Chairman and CEO of Exxon Mobil Corporation. The think tank receives funding from multiple defense contractors, and according to the NY Times, the Chinese Government. This is not a reliable source for information about the environment.

China is big and complicated, and their impact on climate change is likewise complicated. Yes, there are major investments in renewables, but there is also a heckton of coal and other nasties. The government is riven with corruption, making reliance on reported figures a dubious proposition. Many supposedly closed coal plants, for example, are still in operation. In 2015, they led the world with $1.4 trillion in subsidies for fossil fuels, according to the IMF. And recent data shows that the trend in China has reverted to an increase in use of coal. Therefore the science-based “climate action tracker” ranks China’s current status as “highly insufficient”.

This reliance on poor-quality sources is bad journalism, and if that were all, it would be unremarkable. There are plenty of bad articles published every day. The problem is that it fuels a narrative about young people that will only further alienate them.

The olds, like me, have had our fun. We’ve flown where we want, consumed what we want, and enjoyed the benefits of industrialized technology. And in doing so we raise a spectre of fear in our young people, who quite rightly look at the state of the world and wonder if it can all go on.

Is it right to say that doom is inevitable? I’m a Buddhist: the future is uncertain. It’s a matter of probability, and a reasonable person must accept that there is a chance that doom is coming within the lifetime of people alive today.

The chance of the world ending in our lifetimes must be more than zero, ever since the “greatest generation” decided to create world-destroying nuclear arsenals and boomers put them in the hands of leaders of dubious appetites and unconstrained immorality. The end of the world is no longer in the sphere of religious fanatics, but of cold science and mental pathology. The world could end at any moment, and our only bulwark is our trust that Trump and Putin will do the right thing. But Trump and Putin are malevolent psychopaths, and they will never do the right thing.

So if the end of the world must have greater than zero probability, what is it? 1%? 10%? 80%? What exactly is an acceptable risk? What kind of probability of the end of the world is sufficient that a reasonable person would not fall into despair?

How about 0%? Generations have lived under the shadow of the human-caused annihilation of everything. Have we become so numb to this abnormality? Is not this numbness itself a sign of mental and moral pathology? Might despair be a perfectly natural and normal symptom of a mind that is gaining a sense of moral proportion?

Our moral systems were developed in less urgent times, when a war meant the death of thousands, and an environmental problem was the loss of beauty in landscape. Young people are forging a new morality for new circumstances. We can keep preaching at them as if we have a right to imagine we have a solution, or we can try listening. Maybe we have something to learn.

The article quotes from only a few young people. Rather oddly, the views expressed by the young people, though much fretted-upon, don’t really sound problematic if you listen closely. Siddharth Namachivayam, a college junior in California, remarks:

I guess, yeah, it’d be marginally better if Biden was president, but I don’t think Biden being president is more important than the Green party growing in the next couple of years.

This is arguable, and conventional political wisdom would disagree: you can vote for Biden and support the Greens Party. But it is the opinion of someone who is thinking about long-term strategy, not giving up. Conventional wisdom has brought us to this point, so, regardless of the merits of this particular stance, looking for long-term systematic change is a perfectly reasonable response. Rather than condemning him as a “doomer”, maybe we could admit that our short-termism is the cause of the problem, and his longer-term view could be the seeds of something meaningful? Maybe if we had thought more like him, we would have made the systematic changes that would have avoided the nightmare we’re in today?

Max Bouratoglou, a 19-year-old student in California, has a very different take on planning for the long-term:

You’re not seeing people who are planning for the future, because the future seems so precarious and so unpredictable.

Clearly this is reasonable. The amount of chaos in the system is growing at such a rapid rate that planning for the future is very problematic. We are in 2020: all of our plans have been thrown out the window for the whole year. There is no reason to think that the uncertainty of 2020 is an exception. On the contrary, while there will be ups and downs, the long-term trend is towards increasing chaos and uncertainty. What Max is talking about is a reasonable adjustment to the conditions that he find himself in. If we don’t like the fact that our kids think they’ll live in a dystopian future, maybe rather than complaining about them, we could instead try not creating that future?

On having children, he says:

Considering how nihilistic I feel about the future and how I will be immediately affected, do I wanna rain that burden upon someone else?

I think we need to ask ourselves what exactly the issue is here. Is it the folly of the youth? Or perhaps might we ask ourselves, who are we that created a world that forces young people to think about such things?

Going forward, no generation will be able to have a child without facing at least the possibility that the world they will live in is not what it should be. The articles by Gemma Carey in the Guardian on her decision to have a child, and the subsequent tragedy amid the Australian bushfires, offer a sensitive and intelligent reflection on this existential crisis. Young people should be complaining about homework and not getting dates. They shouldn’t have to worry about the end of the world: but they do.

In this, the issue of the most deeply personal decision is intertwined with the welfare of all. To be clear, population growth is itself not a major driver of climate collapse, as most population growth is in underdeveloped countries, where the per-capita carbon output is minimal. But population growth in California certainly is, since the richest 1% create over twice the emissions of the poorest 50%. And to see young people wrestling with these very urgent issues is essential. It shows that they are seeing their future as interconnected with the future of the planet. This is not a problem, it is the solution.

This points to the basic fallacy of Mann’s critique. There is no direct line between a belief in the likelihood or otherwise of climate collapse, and one’s own actions to try to prevent that or not. Religious teachers are something of experts in this field, because we’re been teaching the whole “love triumphs over hate!” idea for thousands of years and, well, here we are. We know all too well that there’s no simple relation between beliefs and actions. People who believe a collapse is likely are diverse, and they do all kinds of different things. Among that spectrum, it is perfectly reasonable to believe that (a) collapse is likely, and (b) we should do what we can to stave it off as long as possible and make it no worse than it need be. It is all about probabilities and margins.

It’s not as simple as that, sure, and not everyone will respond in the same way. But so what? Nothing is simple, and there is no field of human activity where everyone responds the same way. Is there any empirical proof that the acceptance of probable climate doom is, in fact, linked to to a long term decline of mental health or of activism? And if so, is there any evidence that the most effective way to respond to that is to tell doomers they’re wrong, rather than engage with their beliefs in a constructive way?

I would argue that the other side of the equation is vastly more important. The denial of the reality and the seriousness of climate collapse creates a psychic split, and that itself manifests in unhealthy reactions at the psychological and sociological level. In fact, I believe that the current global rise of authoritarianism and delusional thinking is an inevitable psychological outcome of climate denialism. You lock it away, it curdles and comes out worse than before.

One of Jem Bendall’s points is that we should deeply consider how we live, and make choices about our lives that lead to both flourishing and meaning in the present, and the possibility of survival in the case of collapse.

Bendall also points out that despair is not always bad. It is risky and unpleasant, to be sure; but in the spiritual path it may be a time of great uncertainty leading to renewal and transformation.

Perhaps the real problem is not the despair of the youth, but the belief of the adults that “we can fix it”. This is the quintessential view of the modernist industrial/technological world. In slower, saner times, people were more willing to sit and let the seasons “turn, turn, turn”. Every religion has a place it in for the acceptance of the deep reality that our power is limited and we cannot change everything.

This is simple common sense, but it goes against the modern myth of “empowerment”. If we tell every child that “one person can change the world”, are we not forgetting that there are eight billion “one persons” in this world, and statistics suggest that almost none of them will, in fact, change the world? And are we so eager to instill the feeling of power that we forget that those who, history teaches us, actually have power are, by and large, the ones with the money, the property, and the guns?

In my day, it was Anarchy in the UK that got the grownups all fretting about the youth. Pink Floyd got a bunch of kids to turn over desks and yell, “We don’t need no education!” These days the youth really have got something to freak out about. Let them. At the very least, they’ll probably make some cool albums.