Things as they are

22 February 2020A Buddhist monk’s view of the climate emergency.

There comes a time when, after a very long period has passed, a seventh sun appears. This great earth and Sineru the king of mountains erupt in one burning mass of fire. And as they blaze and burn the flames are swept by the wind as far as the Brahmā realm. Sineru the king of mountains blazes and burns, crumbling as it’s overcome by the great fire. And meanwhile, mountain peaks a hundred leagues high, or two, three, four, or five hundred leagues high disintegrate as they burn. Who would ever imagine that this earth and Sineru, king of mountains, will burn and crumble and be no more, except for one who has seen the truth?

—The Buddha, AN 7.66, The Seven Suns

As a Buddhist monk, I have practiced to see things as they are. To accept what is real and true, without rejecting what I do not like or embracing what I find amenable. I have also meditated for many years on deep compassion, on seeing the value of all life first and foremost, and respecting the role of humanity as carers and custodians. My relation with nature is not that of a farmer or a gatherer, a fisher or a miner. Although my spiritual life would not be possible without the material support of those who make use of the land, I don’t see the earth primarily as a source of food, income, or resources, but as a source of wonder and spiritual renewal. And so I have lived in forests for much of my life in search of peace. Now I live in the city, partly because I don’t know that the forest life in Australia has a future. There is a balance in all things, between the spiritual and the material, the forest and the city, the life of renunciation and the life of accumulation, and I fear that balance has been lost.

We humans are pretty efficient at filtering out things we don’t want to hear. Despite decades of messaging, it’s still possible to go through life not know anything much about our climate crisis. Few are really prepared to change, or for change. I’ve been involved in the environmental movement in one way or another since the early 1980s, and it is clear that, whatever our successes in other areas, we have failed on the big one. The scientists and engineers have done their jobs, but it hasn’t translated into the kind of change we need. How do we change so many people so far so fast, and implement that change in effective policy? The whole thing is so unprecedented, so vast, we just don’t know what will work. And it is sheer naivety to dismiss the possibility that there simply is no solution; that we are rushing headlong to our own self-created annihilation and will just keep on going. I don’t know, and I doubt anyone else does either. I do believe, though, that whatever happens, and whatever we do or don’t do about it, it is better to be informed than to be ignorant.

I am no expert, just a little piece of planet earth that has somehow managed to become sentient, and who has used some of that sentience to read about climate change. Over the years I have benefited from articles that gather up-to-date reports in one handy place. The first and most impactful for me was An introduction to global warming impacts: Hell and High Water, a 2009 article in ThinkProgress by Joe Romm. It’s ten years old, but still well worth reading. I thought I’d do something similar, so I could learn some more and maybe help some folks get up to speed. Many of these links were sourced from a scrappy post that went viral during the Australia bushfires of 2019/2020, The future is grim. I have tried to favor original sources, but a well-written media report is often more palatable than a scientific journal. There are over 350 articles linked here, loosely gathered by topic, but still it covers only a small portion of the climate news. And there is a recency bias, as I have focused on news over 2019–early 2020. If you want to keep up with events, The Guardian has the best mainstream coverage of the climate crisis.

This is a litany of facts, sprinkled with a little of my own commentary. Ignore my thoughts if you like, they are not important: the earth is. It can be quite distressing to learn about the state of our planet, so you probably want to read in moderation. The sky is still blue (in some places), there is still water to drink (if you’re lucky), and the air can be breathed (on a good day). Whatever the blessings that life gives you, enjoy them while you can. Mother Earth wants us to be happy. But she also wants us to, you know, stop shitting on her. So best do that then.

- Erika Reinhardt: A Data-Driven Guide to Effective Personal Climate Action.

Global summary

No survey or summary can do justice to the harms inflicted on our living planet by human industrial activity. There are too many things, effects strange and unexpected, local conditions that no-one could have forseen. One thing we do know above all else: it’s bad and it’s getting worse.

Overall

I’m beginning this list with a quote from the U.S. Army War College. I’m a life-long pacifist, and this is a nod to the fact that, although the environment has become a politically polarized issue, reality doesn’t care about our politics. Even the institutions most closely associated with the exertion of power, imbued with the ethos that they can bend circumstances to their will, must eventually face a reckoning. The U.S. military, quite apart from its humanitarian record, is one of history’s greatest CO₂ emitters. Yet they acknowledge that the environment is something beside which all their guns and bombs are powerless.

- U.S. Army War College with NASA: “Sea level rise, changes in water and food security, and more frequent extreme weather events are likely to result in the migration of large segments of the population. Rising seas will displace tens (if not hundreds) of millions of people, creating massive, enduring instability. This migration will be most pronounced in those regions where climate vulnerability is exacerbated by weak institutions and governance and underdeveloped civil society. Recent history has shown that mass human migrations can result in increased propensity for conflict and turmoil as new populations intermingle with and compete against established populations. More frequent extreme weather events will also increase demand for military humanitarian assistance. Salt water intrusion into coastal areas and changing weather patterns will also compromise or eliminate fresh water supplies in many parts of the world. A warming trend will also increase the range of insects that are vectors of infectious tropical diseases. This, coupled with large scale human migration from tropical nations, will increase the spread of infectious disease. Arctic ice will continue to melt in a warming climate. The increased likelihood is of more intense and longer duration drought in some areas, accompanied by greater atmospheric heating.”

- Guardian: The Uninhabitable Earth by David Wallace-Wells review—our terrifying future. “You already know the weather has gone weird, the ice caps are melting, the insects are disappearing from the Earth. You already know that your children, and your children’s children, if they are reckless or brave enough to reproduce, face a vista of rising seas, vanishing coastal cities, storms, wildfires, biblical floods. … David Wallace-Wells is here to tell you that ‘It is worse, much worse, than you think.’” “Absent a significant adjustment to how billions of humans conduct their lives, parts of the Earth will likely become close to uninhabitable, and other parts horrifically inhospitable, as soon as the end of this century.”

- Guardian: ‘The only uncertainty is how long we’ll last’: a worst case scenario for the climate in 2050. The Future We Choose, a new book by the architects of the Paris climate accords, offers two contrasting visions for how the world might look in thirty years.

- Carbon Brief: Interactive: The impacts of climate change at 1.5°C, 2°C and beyond. Carbon Brief has extracted data from around 70 peer-reviewed climate studies to show how global warming is projected to affect the world and its regions.

- National Academy of Sciences: Irreversible climate change due to carbon dioxide emissions. Climate change that takes place due to increases in carbon dioxide concentration is largely irreversible for 1,000 years after emissions stop.

- ThinkProgress: Scientists write dire letter to the future about climate change. “We know what is happening and know what needs to be done. Only you know if we did it.”

- MSNBC via Youtube: Katy Tur speaks with Michael Mann on the scientific and emotional challenge of climate change. “How pointless are my decisions when we are not focused on climate change.”

The state of the climate

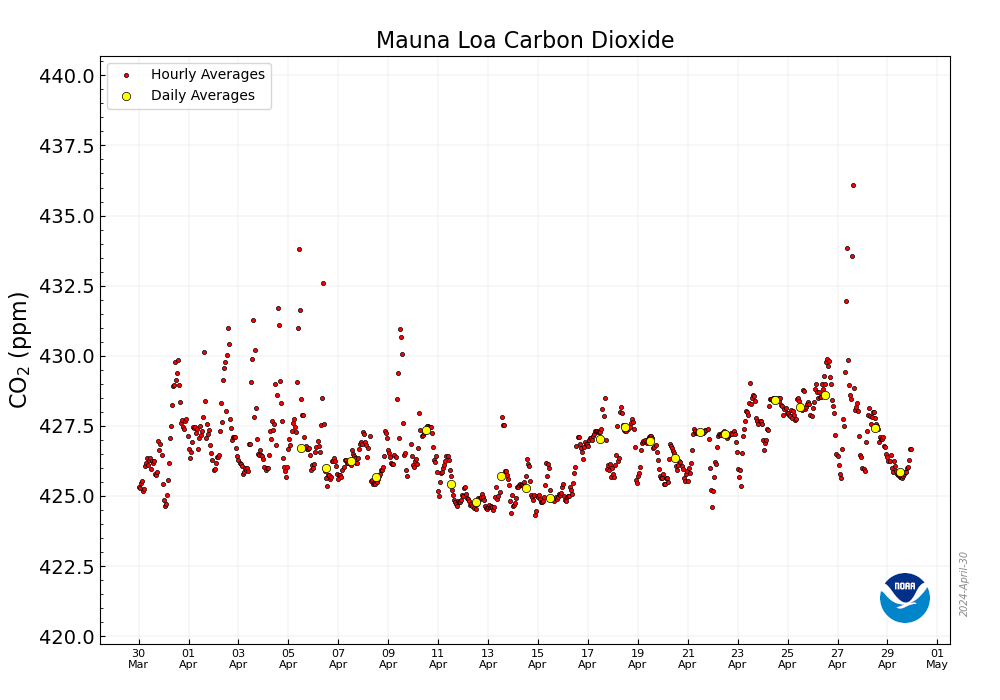

Don’t be fooled by the details. Don’t be distracted by the latest news-of-the-day. The chart that matters is the one below: how much CO₂ is in the atmosphere. It is CO₂ that is the primary driver of global warming, and this one measure—the Scripps CO₂ program at Maunua Loa, maintained since 1958—is both crucially important in itself, and provides a proxy for the state of play.

It’s easy to be impressed by reports of new technologies, or a flatlining of emissions in some sectors. However, emissions are not just produced by industry or transport or the energy sector, but by melting tundra and burning forests as well. And they do not exist in a vacuum; the earth’s systems are dynamic, and carbon is being absorbed as it is being emitted. It’s complicated. Many factors are beyond our control, and many are subject to little-understood feedback effects.

The global atmospheric CO₂ reflects all the CO₂ put into the atmosphere from every source, as well as all the CO₂ that is removed. And as you can see, the news isn’t great: CO₂ continues to rise and even accelerate, the gentle upwards curve belying the idea that somehow we have it all under control.

The world is not ours. It belongs to no person, no nation, no corporation. It is our conceit telling us we have the right to control it, and our delusion pretending we have the means to bend it to our will. When we grok that, we have taken the first step towards wisdom.

- NOAA: Atmospheric CO₂ levels continue to rise. In January 2020 the global monthly CO₂ level was 413.40ppm, up from 410.83ppm the year before. (I had to revise this upwards while writing this essay.)

- NOAA: CO₂ hits daily record 416.08ppm on Feb 10 2020. (I also had to revise this upwards while writing.)

- Climate Levels: Other greenhouse gases CH4 and N02 are rising along with CO₂, driving temperature increase and sea level rise, as oxygen falls.

- Our World in Data: 2017 data shows CO₂ emissions rising.

- CSIRO: 2019 Global CO₂ emissions set to reach all-time high.

- NASA: Global mean warming is currently around 1°C and rising.

- NOAA via Guardian: Scratch that—as of Jan 2020 global mean was up 1.14°C. “The past five years and the past decade are the hottest in 150 years of record-keeping.” In much of much of Russia, Scandinavia, and eastern Canada temperatures were 5°C above average. “However, planet-warming emissions from human activity are not showing any sign of decline, let alone the deep cuts needed to meet the 2°C goal and address the climate crisis. According to scientists, the world must halve its emissions by 2030 to stand any chance of avoiding disastrous climate breakdown.”

- IPCC: Temperatures over land are rising faster than over sea.

- IUCN: 93% of potential atmospheric heating caused by emissions since the mid-20th century has been absorbed by the ocean.

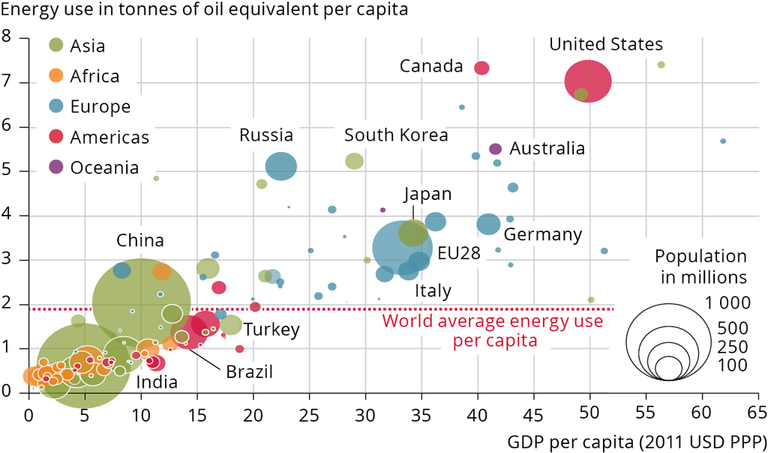

- Resource Panel: Despite efforts to “decouple”, global economic growth remains coupled to energy use and material extraction.

- Guardian: Antarctic temperature rises above 20°C for first time on record. Scientists describe 20.75°C logged at Seymour Island as “incredible and abnormal”.

- Washington Post: The Arctic may have crossed key threshold, emitting billions of tons of carbon into the air, in a long-dreaded climate feedback. The Arctic is undergoing a profound, rapid and unmitigated shift into a new climate state, one that is greener, features far less ice and emits greenhouse gas emissions from melting permafrost.

- European Geosciences Union: New study—Fracking prompts global spike in atmospheric methane.

Emissions: it’s not just power, cars, and planes

The basic CO₂ equation: emissions grow as absorption declines. Attention usually focuses on obvious things like energy production and transport, and while these are important, there are plenty of other sources of emissions both human and natural. Heavy industry, meat, construction, and the military all produce vast amounts of CO₂. Meanwhile, natural sources of CO₂ and methane appear dangerously close to irreversible tipping points, where climate disruption upsets the “normal” equilibrium, creating massive new surges of greenhouse gases.

Preventing climate collapse is a lot harder than just putting up some solar. The ultimate culprit is our industrialized economy. Setting aside the details of technology and policy, what industrial society does is harness the element of fire to transform matter on an unprecedented scale. So long as we follow this path, we will be forcing nature down a road she does not want to take. Smarter technologies may allay the trauma, but without a radical change of values I fear we will simply face a new crisis a few years down the road.

- Phys.org: Cargo ships are emitting boatloads of carbon, and nobody wants to take the blame. “Hauling goods around by sea requires roughly 300 million tons of very dirty fuel, producing nearly 3 percent of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions, giving the international maritime shipping industry roughly the same carbon footprint as Germany.”

- Time: The Triple Whopper Environmental Impact of Global Meat Production. Livestock production may have a bigger impact on the planet than anything else.

- Food Navigator: Meat and seafood consumption in Asia will rise 78% by 2050.

- Guardian: Revealed: The 20 firms behind a third of all carbon emissions.

- Guardian: Meat company faces heat over ‘cattle laundering’ in Amazon supply chain. “Investigative work by the Guardian, Repórter Brasil and the Bureau of Investigative Journalism showed the way that global meat demand was driving Amazon deforestation and revealed that fires were three times more common in Amazon beef farming areas.”

- QZ: The US military is a bigger polluter than more than 100 countries combined.

- BBC: Concrete: The massive CO₂ emitter you may not know about. Cement is the source of about 8% of the world’s CO₂ emissions. If the cement industry were a country, it would be the third largest emitter in the world.

- New Scientist: Steel and concrete are climate change’s hard problem. Can we solve it?

- OilPrice: Hollywood’s Huge Carbon Footprint. The Hollywood film and television industry produces more air pollution in the five-county Los Angeles region than almost all of the other five sectors studied.

- Vox: This climate problem is bigger than cars and much harder to solve. Low-carbon options for heavy industry like steel and cement are scarce and expensive. Heavy industry is responsible for around 22 percent of global CO₂ emissions. Report: “The pathway toward net-zero carbon emission for industry is not clear, and only a few options appear viable today.”

- Phys.org: NASA flights detect millions of Arctic methane hotspots.

- Yale: As Climate Change Worsens, A Cascade of Tipping Points Looms. New research warns that the earth may be approaching key tipping points, including the runaway loss of ice sheets, that could fundamentally disrupt the global climate system. A growing concern is a change in ocean circulation, which could alter climate patterns in a profound way.

- Guardian: Climate emergency: world “may have crossed tipping points”. The world may already have crossed a series of climate tipping points, according to a stark warning from scientists. This risk is “an existential threat to civilisation”, they say, meaning “we are in a state of planetary emergency”.

Current predictions

Prediction is an ancient art. 2,500 years ago, the Buddha spoke of a time when the waters would rise and drown the lands; of a time when the heat would grow out of control and nations would be devastated by an inferno of flame. Not that the Buddha claimed to see the future, but he understood cause and effect. The conditions that we take as normal are but a short chapter in the earth’s long story. The world we know evolved from complex interactions of nature that include human activity. And if human activity changes drastically, as it has done in the industrial era, one chapter may finish and another begin. Whether our story continues in the next chapter is as yet unclear.

Modern predictions are scarcely less dramatic, but considerably more precise. On the whole, scientific predictions since the 1970s have been fairly accurate. The IPCC reports are couched in a highly complex language of conditionality, reminding us that the future is not set in stone but is determined by the choices we make today. Arrived at via a painstaking process of consensus, which requires accommodating denialist governments from Saudi Arabia and Australia, the mainstream science has proven to be on the whole quite accurate. Meanwhile, some scientists, such as NASA’s James Hansen, argue that there is an overall bias towards conservatism in science, and the real picture is considerably more severe. Time will tell, I guess, so long as someone is left alive to read the instruments.

- NASA: Historical predictions of global warming have been generally accurate.

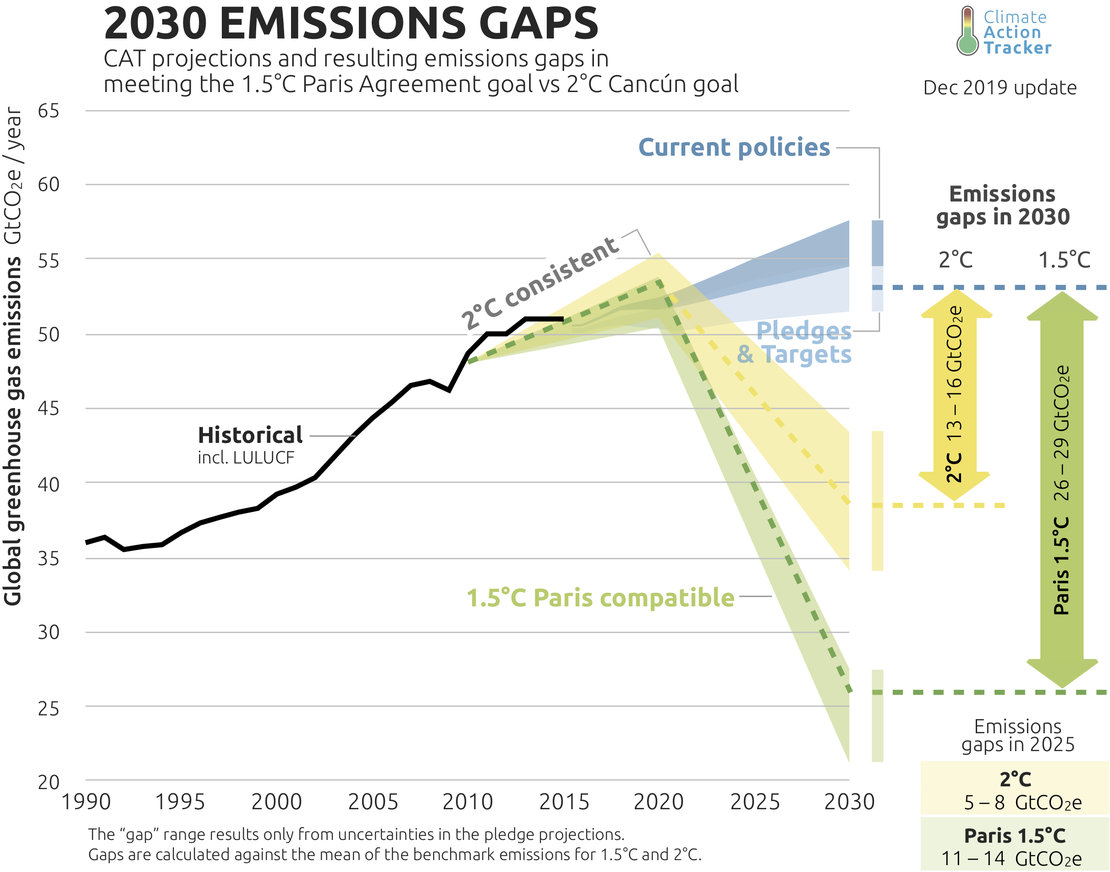

- Climate Action Tracker: We are currently on course for a rise of 3°C or more by the end of the century.

- Carbon Brief: Preliminary findings from latest climate models predict significantly higher end-of-century warming than older models (CMIP6 averages in 2019: 1.8°C–5.6°C vs. IPCC AR5 in 2013: 1.5°C–4.5°C). We are currently tracking the highest emission scenario, with possible (unaveraged) outcomes between 2.6°C–7.4°C.

- UCSD: Continued expansion of energy use, including renewables, must result in an uninhabitable planet within a few hundred years.

- Phys.org: Global temperature targets will be missed within decades unless carbon emissions reversed: new study.

- Washington Post: We may avoid the very worst climate scenario. But the next-worst is still pretty awful.

- New York Times: The End of Australia as We Know It. Fueled by climate change and the world’s refusal to address it, the fires that have burned across Australia are not just destroying lives, or turning forests as large as nations into ashen moonscapes. They are also forcing Australians to imagine an entirely new way of life.

- Brussels Times: Floods, droughts, fires: Europe’s climate change future. “We need to prepare today to prevent the disappearance of entire regions.”

- Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics: Ice melt, sea level rise and superstorms: evidence from paleoclimate data, climate modeling, and modern observations that 2°C global warming is highly dangerous. “Continued high fossil fuel emissions this century are predicted to yield (1) cooling of the Southern Ocean, especially in the Western Hemisphere; (2) slowing of the Southern Ocean overturning circulation, warming of the ice shelves, and growing ice sheet mass loss; (3) slowdown and eventual shutdown of the Atlantic overturning circulation with cooling of the North Atlantic region; (4) increasingly powerful storms; and (5) nonlinearly growing sea level rise, reaching several meters over a timescale of 50–150 years.”

- Global Environmental Change: Climate change prediction: Erring on the side of least drama? Scientists are biased not toward alarmism but rather the reverse: cautious estimates that err on the side of less rather than more alarming predictions.

Current response

In a word, inadequate. Nations hold grand meetings at which they publicly proclaim their determination to fight climate change, while privately fighting among themselves for who gets to emit the most carbon. The basic metric is the “carbon budget”, a reductive term that reflects how totally our love and reverence for our living planet has been subsumed by economic rationalism. Increasing your “carbon budget” is a win, because you get to emit more, destroy more of the planet, and make more money. The end result of all this is that nations make pathetically small, non-binding commitments, then fail to keep them.

In traditional Buddhist cultures I have seen how elders are honored with love as our mothers and fathers. Caring for them is a privilege that can scarcely begin to repay the debt of gratitude we owe. I wonder what the international process would look like if, instead of treating our planet as a resource to be spent, and complaining about the burden of caring for her, we honored her as our Mother, and took loving care of her with joy in our hearts.

- UN Environmental Program: Emissions Gap report 2019. “If current unconditional national commitments are fully implemented, there is a 66 per cent chance that warming will be limited to 3.2°C by the end of the century.”

- Climate Action Tracker: Global commitments fall far short of keeping us on 1.5°C rise, or even 2°C.

- Climate Action Tracker: Pledges for action by almost all countries are insufficient.

- Rainforest Action Network: 33 global banks have provided $1.9 trillion to fossil fuel companies since the adoption of the Paris climate accord.

- MIT Technology Review: “Our pathetically slow shift to clean energy.”

- BP: The share of carbon-free electricity has barely budged.

- Bloomberg via MIT: EVs are still a sliver of total auto sales.

Effects on Nature

Nature is us; we are a part of nature. This truth has been self-evident to me my entire adult life. But as the wonderful Koyaanisqatsi showed us many years ago, our lives are out of balance. We think we can consume without thought and never suffer the consequences. Nature, vast and abundant as she is, has her limits, and we are breaking them.

The animals are dying; except cows, sheep, chickens, and pigs

Humans are animals, and it has become increasingly difficult to point to a specific biological feature that sets us apart from the rest of the animal kingdom. One thing indisputably unique about us, however, is our creation of industrial society and our employment of that to bend nature to our will. The good news is, not all humans have felt such a separation from our animal brothers and sisters. I was once told by Ken Colbung, an aboriginal elder of the Nyoonga people, that he was vegetarian because his people would never kill an animal unless it was necessary to survive. Times have changed; for us to survive, it is necessary not to kill, but to stop killing animals. But it seems most of us have not got the memo yet.

- UN via CNN: Almost a third of the Earth will need to be protected by 2030 and pollution cut by half to save our remaining wildlife, as we enter the planet’s sixth era of mass extinction, according to UN Convention on Biological Diversity.

- Guardian: Since the rise of human civilisation 83% of wild mammals have been lost.

- Guardian: Humanity has wiped out 60% of mammals, birds, fish and reptiles since 1970, leading the world’s foremost experts to warn that the annihilation of wildlife is now an emergency that threatens civilisation.

- Business Insider: A million species are at risk. “18 signs we’re in the middle of a 6th mass extinction”.

- Center for Biological Diversity: Over 1 million species are on track for extinction in coming decades.

- Gizmodo: Species declared extinct in the 2010s.

- CNN: A blob of hot water in the Pacific Ocean killed a million seabirds, scientists say.

- Guardian: The insect apocalypse. “we may have lost 50% or more of our insects since 1970—it could be much more”.

- Science Direct: Decline of insects threatens a catastrophic collapse of nature’s ecosystems. This is not just due to climate change; in order of importance, drivers are:

- habitat loss and conversion to intensive agriculture and urbanisation;

- pollution, mainly that by synthetic pesticides and fertilisers;

- biological factors, including pathogens and introduced species; and.

- climate change.

- Guardian: Car ‘splatometer’ tests reveal huge decline in number of insects … up to 80% in two decades.

- Guardian: Fates of humans and insects intertwined, warn scientists. “The current [insect] extinction crisis is deeply worrisome. Yet, what we know is only the tip of the iceberg. … Insect declines lead to the loss of essential, irreplaceable services to humanity. Human activity is responsible for almost all current insect population declines and extinctions.”

- Guardian: Firms making billions from ‘highly hazardous’ pesticides, analysis finds. Use of harmful chemicals is higher in poorer nations. … A report in 2017 co-authored by UN special rapporteur Baskut Tuncak accused pesticide companies of the “systematic denial of harms”, “aggressive, unethical marketing tactics” and lobbying of governments, which has “obstructed reforms and paralysed global pesticide restrictions”. It also said the idea that pesticides were essential to feed a fast-growing global population was “a myth”.

- QZ: It’s not just animals: “Biodiversity loss, together with climate change, are some of the biggest challenges faced by humanity. Along with human-driven habitat destruction, the effects of climate change are expected to be particularly severe on plant biodiversity. Current estimates of plant extinctions are, without a doubt, gross underestimates.”

- Guardian: 'They define the continent': nearly 150 eucalypt species recommended for threatened list. Scientists’ call follows national assessment that finds gum trees in Western Australia wheat belt suffering worst rate of decline.

- Population and Development Review: Harvesting the Biosphere: The Human Impact. “the unprecedented domination by a single species and its associated domesticated zoomass”

- The Week: Amazon deforestation, mostly due to cattle, is accelerating again amid massive fires: “Over the past half century, though, one-fifth of the rain forest—300,000 square miles, an area larger than Texas—has been deforested.Scientists say if another 10 percent is lost, the ecosystem will reach a tipping point at which it will dry up irreversibly, converting the entire remaining rain forest into a savannah.”

- The Age: Toll of bushfires in south-east Australia in 2019/2020: Euan Ritchie, associate professor of wildlife ecology at Deakin University, says of the “Realistically, the number of animals killed in these fires is many, many, many billions.”

- Financial Express: From 40 million to less than 400,000, Vulture population is dwindling in India.

- CNN: Many species of firefly at risk of extinction due to loss of their natural habitats, pesticide use and artificial light.

- Guardian: Bumblebees’ decline points to mass extinction. “We found that populations were disappearing in areas where the temperatures had gotten hotter. If declines continue at this pace, many of these species could vanish forever within a few decades.”

- NYT: Can the World’s Strangest Mammal Survive? The platypus is imperiled by habitat loss, predation by feral cats, and now drought and wildfires wrought by climate change.

- National Academy of Sciences: Biological annihilation via the ongoing sixth mass extinction signaled by vertebrate population losses and declines. Dwindling population sizes and range shrinkages amount to a massive anthropogenic erosion of biodiversity and of the ecosystem services essential to civilization.

The oceans: heating, rising, and dying

In the psychology of Carl Jung, the ocean is the great symbol of the unconscious. And as so often, the metaphors employed by the mind reflect a much more concrete material reality. We only see the shining surface of the seas and remain largely ignorant of what happens underneath. Yet most life lives in the seas, and they will be at the forefront of our survival or annihilation. Staggering under the multiple impacts of heating, acidification, pollution, and overfishing, the dread specter of desertified oceans looms.

- Alaska Public: Extremely low cod numbers lead feds to close the Gulf of Alaska fishery for the first time. “Next to no” new cod eggs. “What the climate scientists are showing us is that this is going to be the new average within a short time frame.”

- Oceana: Thirty-three percent of global fish stocks are now overfished, a figure that is increasing year after year and which poses a threat to the marine ecosystem and food security for billions of people worldwide.

- Foreign Policy: Asia Is Trawling for a Deadly Fishing War. Growing tensions between Sri Lankan and Indian fishermen are just one signal of a looming conflict over the region’s depleted waters.

- Independent: A quarter of world’s seafood is caught using destructive bottom-trawling responsible for habitat loss. 14% of the seafloor shallower than 1,000m is trawled.

- Australian Broadcasting Commission: An unprecedented succession of coral bleaching events has left reefs around the world in a catatonic state. Almost half the Great Barrier Reef has been reduced to a coral graveyard.

- Guardian: A quarter of world’s seafood is caught using destructive bottom-trawling responsible for habitat loss. 14% of the seafloor shallower than 1,000m is trawled.

- IUCN: Great Barrier Reef on brink of third major coral bleaching in five years, scientists warn. If ocean temperatures don’t drop in the next two weeks, heat stress could tip reef over into another widespread event. “We are down to the wire.”

- U Plymouth: Dead zones could be expanding much faster than previously thought, and future calculations must take bacteria into account in order to accurately predict the full impacts of climate change and human activity on the marine environment.

- Science via Guardian: Fishery collapse ‘confirms Silent Spring pesticide prophecy’. “A fishery that was sustainable for decades collapsed within a year after farmers began using neonicotinoids.”

- Vice: The Blood Pipe Is Still Spewing Blood After Nearly Two Years. “2019 was the worst sockeye salmon return in Canadian history. This is what extinction looks like and it’s happening right under our noses.”

- Stanford University via Vice: The devastation of the vast majority of the world’s marine life is much closer than we think. “The patterns of warming, and loss of oxygen from the ocean that can account for the extinction [of the dinosaurs] are the same features we’re starting to see right now.”

- Guardian: Ocean acidification can cause mass extinctions, fossils reveal. “Scientists said the latest research is a warning that humanity is risking potential ‘ecological collapse’ in the oceans, which produce half the oxygen we breathe.”

- CBC: Building blocks of ocean food web in rapid decline as plankton productivity plunges.

- Scientific American: Phytoplankton Population Drops 40 Percent Since 1950.

- Nature Climate Change via The Conversation: Acid oceans are shrinking plankton, fuelling faster climate change. “significant ecological implications of climate change will take effect much sooner than previously anticipated”

- Macquarie University via The Independent: Plastic pollution harms bacteria that produce 10 per cent of oxygen we breathe, study reveals.

- Vice on HBO: Our oceans are rising. With human use of hydrocarbons skyrocketing, waters around the globe are getting hotter and, now, this warm sub-surface water is washing into Antarctica’s massive western glaciers causing the glaciers to retreat and break off. Antarctica holds 90% of the world’s ice and 70% of its freshwater, so if even a small fraction of the ice sheet in Antarctica melts, the resulting sea level rise will completely remap the world as we know it.

- Science Daily: Using data from European satellites, a student has demonstrated that the global sea level rise has accelerated over the past four decades.

- NY Times via Today Online: Rising seas will erase more cities by 2050, new research shows.

- Nature Communications: New elevation data triple estimates of global vulnerability to sea-level rise and coastal flooding. “Under high emissions … 630 million people live on land below projected annual flood levels for 2100, and up to 340 million for mid-century”

- Forbes: Shocking New Maps Show How Sea Level Rise Will Destroy Coastal Cities By 2050.

- Guardian: The three-degree world: the cities that will be drowned by global warming. (Note: the graphics here are excellent, but this predates the Nature Communications study that shows sea level rise will be much greater.)

- ASEAN Post: Among the major ASEAN cities that could potentially be submerged by 2050 include Bangkok, Jakarta, Ho Chi Minh City and Manila.

- Climate Central: Interactive map showing regions inundated by 2050.

- CNN: Oceans are warming at the same rate as if five Hiroshima bombs were dropped in every second. 2019 sets record ocean heating level.

The future of water: floods and drought

There is no simple way to predict changes in our rainfall and water supplies. Sometimes dryer, sometimes wetter; but at all times, greater unpredictability, harsher extremes, and less time to recover or find balance. That means a harder life for all farmers, for emergency services, and for all of us who depend on them.

In a Singapore apartment one morning, I had the chance to discuss Singapore’s climate change response with a senior civil engineer. As Singapore is a relatively rational society, there is none of the denialist nonsense to deal with, and lots of ambitious ideas planned or proposed. The apartment, like many that morning, was flooded after heavy rains. That wasn’t supposed to happen, I was told. They were designed for a hundred year flood, and now it’s every three or four years. It highlighted the uncertainty of ambitious engineering plans in an uncertain future. Raise coastal roads by a meter (but won’t sea level will rise more than that?) Build a floating airport (will anyone still be flying?)

The real adaption is not to heat or sea level or fire, but to chaos.

- Guardian: Inside Australia’s climate emergency. Dozens of Australian towns have run out of drinking water. This is what happens when the taps run dry.

- Indian Government report: 600 million people in India face high to extreme water stress. 200,000 people die every year due to inadequate access to safe water. The crisis is only going to get worse. By 2030, the country’s water demand is projected to be twice the available supply.

- CNN: 100 million people across India are on the front lines of a nationwide water crisis. A total of 21 major cities are poised to run out of groundwater in 2020

- Vox: The severe floods soaking the Midwest and Southeast are not letting up. “NOAA forecast that two-thirds of the contiguous United States would face elevated flood risks”

- National Geographic: Midwest flooding is drowning corn and soy crops. The U.S. Department of Agriculture monitors crop progress during the planting season, and on May 28 they reported that only 58 percent of the corn that could be planted was in the ground. For soybeans, it was only 29 percent. “Overall, it’s climate change,” says Donald Wuebbles, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “We are living climate change right now,” says Evan DeLucia, a plant biologist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign”.

- Weather.com: Record-long Mississippi River flood of 2019 caused by multiple back-to-back heavy rain events.

- Vox: 2019 was a brutal year for American farmers, “a one-two punch of nasty flooding exacerbated by climate change and a trade war with China”

- eNews Channel Africa: Hydrology expert says his research suggests South Africa is experiencing its worst drought in a thousand years.

- Red Cross via News24: 2 million on brink of starvation in regional drought in Zambia.

- Red Cross: In 2019, “a succession of cyclones and floods has already resulted in significant loss of life and assets in Malawi, Mozambique, South Africa and Zimbabwe … Climate change-induced natural disasters in Southern Africa are often invisible in the global media, even though they are protracted and threaten the livelihoods of millions.”

- The Institute of International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict at the University of Bochum via DW: Water shortages pose growing risk to global stability. Climate change has increased global water security issues and made society more vulnerable to natural disasters.

- UN: With the existing climate change scenario, almost half the world’s population will be living in areas of high water stress by 2030.

- World Resources Institute via Welt.de: 33 countries threatened by water shortages by the year 2040.

- Aqueduct: Interactive water risk atlas.

- Guardian: Queensland school runs out of water as commercial bottlers harvest local supplies.

- NASA study reported in Washington Post via The Independent: The long and severe drought in the U.S. Southwest pales in comparison with what’s coming: a megadrought that will grip that region and the central plains later this century and probably stay there for decades.

- Truthout: The Looming US Water Crisis.

- Financial Express: Shocking fall in groundwater levels! Over 1,000 experts call for global action on ‘depleting’ groundwater.

- Vox: California’s droughts and deluges are a sign of the weather “whiplash” to come. Climate change isn’t just making weather more extreme. It’s making it more volatile.

- Twitter: In summer of 2019/2020, the record drought, fires, and heat in Australia 2019/2020 were followed by record rain and flood. “Just a few days ago, this region saw the worst #bushfires and now waterfalls”

- Twitter: “Only in Australia.”

Toxic air and chaotic weather

There is nothing more fundamental, nothing we take more for granted, than the air we breath. Millions of people live in places where this most immediate of needs is polluted and degraded. Not only will air continue to get worse in the future, air pollution creates chronic, widespread health effects across the whole population, exacerbating the impact of other threats.

Breathing is the foundation of meditation. The breath that enters us brings life and ease, reminding us that we are still alive. How are we to sooth our anxieties in meditation when we know, in the back of our minds, that every breath is filling us with poison?

- World Health Organization: Air pollution, climate, and health. The equation is simple:

- An estimated 7 million people per year die from air pollution-related diseases. These include stroke and heart disease, respiratory illness and cancers.

+ - Many health-harmful air pollutants also damage the climate. Fine particles of black carbon (soot) from diesel and biomass combustion and ground level ozone are leading examples.

= - Reducing air pollution would save lives and help slow the pace of near-term climate change.

- An estimated 7 million people per year die from air pollution-related diseases. These include stroke and heart disease, respiratory illness and cancers.

- Institure for Advanced Sustainability Studies: Air Pollution and Climate Change. Air pollution and climate change are closely related. As well as driving climate change, the main cause of CO₂ emissions—the extraction and burning of fossil fuels—is also a major source of air pollutants. What’s more, many air pollutants contribute to climate change by affecting the amount of incoming sunlight that is reflected or absorbed by the atmosphere, with some pollutants warming and others cooling the Earth. These short-lived climate-forcing pollutants (SLCPs) include methane, black carbon, ground-level ozone, and sulfate aerosols. They have significant impacts on the climate: black carbon and methane in particular are among the top contributors to global warming after CO₂.

- Air Quality Index Project: Updated information on global air quality.

- Nature Climate Change via The Conversation: Climate change set to increase air pollution deaths by hundreds of thousands by 2100.

- Guardian: Inside Australia's climate emergency: the air we breathe. For months, Australians breathed air pollution up to 26 times above levels considered hazardous to human health. The long-term impact could be devastating. “Millions of people in Canberra, Sydney, and rural towns close to the fires breathed toxic pollution for months. And experts say we don’t yet know what the long-term health effects will be. ‘We’re all currently living in a big experiment. We know it will be bad, we just don’t know how bad,’ says Donna Green, an associate professor at the University of New South Wales’ climate change research centre.

- Reddit: Air pollution in Sydney during 2019/2020 fire season.

- Environmental Defense Fund: How climate change makes hurricanes more destructive.

- Environmental Defense Fund: US had five 1,000-year floods in less than a year. What’s going on? We may already have shifted so far into a new climate regime that probabilities have been turned on their head.

- NPR: When a flash flood ripped through Old Ellicott City in Maryland, residents thought it was a freak occurrence. Instead, it was a hint about the future.

- Washington Post: Storm Dennis, one of the Atlantic’s most powerful bomb cyclones, churns up 100-foot waves and slams U.K.

The planet is on fire

In January 2020 I returned from the fires of Northern California to the devastation of eastern Australia. I have seen over the Blue Mountains, peak after peak, valley after valley, everything black and burned, with nothing remaining but silence and ashes and death.

Though I have read the science, I guess I somehow assumed that climate change would be gradual, that there would be a certain genteel studiedness to it all. The science sounds so civilized. But fire is not civilized.

Perhaps we have been looking at it all wrong. The ancient Indo-European peoples did not study fire as a science, but worshiped it as a God. For a while, He deigned to help us, to smelt our metals and drive our industry. But we forgot our prayers and imagined that we had become the master, bending fire to our will. Fools, the lot of us.

- Aeon: The planet is burning. Wild, feral and fossil-fuelled, fire lights up the globe. Is it time to declare that humans have created a Pyrocene?

- Guardian: Interactive—Counting the cost of Australia’s summer of dread.

- Guardian: “Triple whammy”: drought, fires and floods push Australian rivers into crisis. The combination of extreme weather events will have cascading impacts on fish, platypus and invertebrates, threatening some with extinction.

- New Scientist: Unprecedented Arctic megafires are releasing a huge amount of CO₂. “Dozens of wildfires of an unprecedented intensity have been burning across the Arctic circle for the past few weeks, releasing as much CO₂ in just one month as Sweden’s total annual emissions.”

- Business Insider: The Amazon is losing about 3 football fields’ worth of rainforest per minute. “Carlos Nobre, a senior scientist for INPE, told the World Wildlife Fund. ‘If warming exceeds a few degrees Celsius, the process of “savannisation” may well become irreversible.’”

- Global Forest Watch: Map of world fires.

- Guardian: ‘The devastation of human life is in view’: what a burning world tells us about climate change. “I was wilfully deluded until I began covering global warming, but extreme heat could transform the planet by 2100.”

The poles are melting

At once one of the most visible signs of altered climate, and one of the most distant from most peoples’ lives, images of the melting poles are at the forefront of media coverage. The poles are intimately linked with our lives through multiple mechanisms: plankton, sea currents, weather patterns, sea level, CO₂ release, biodiversity, and even disease. It is only a few short years until the Arctic ice will vanish, changing the very picture of earth from space, while accelerating warming as the reflective advantage of ice is lost. But it is the Antarctic ice that is an even bigger threat.

- Guardian: Last time CO₂ levels were this high. Trees growing near the South Pole, sea levels 20 metres higher than now, and global temperatures 3°C–4°C warmer.

- Nature Climate Change via Global Citizen: Soil in the Arctic Is Now Releasing More Carbon Dioxide Than 189 Countries. The Arctic has changed from a carbon sink to a carbon hose. “The phenomenon taking place in the Arctic is known as a feedback loop. As the planet warms, forests, permafrost layers, glaciers, and more, are releasing more emissions and absorbing more heat, raising global temperatures in the process, and causing more environmental changes to occur—setting in motion a cycle that could soon reach a dangerous runaway point.”

- NASA via Vice on HBO: “Drunken Forests” In Alaska Are Another Sign Of Melting Permafrost. In parts of Alaska, the ground is sinking so much that trees are growing almost horizontally. It’s an area scientists refer to as a “drunken forest.”

- Moscow Times: Scientists Discover Record Methane Emission in the Russian Arctic. “No one has ever recorded anything like this before.”

- IFL Science: In response to Stockholm University reporting “vast methane plumes escaping from the seafloor” in the Arctic Ocean, Professor Jason Box of the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland tweeted “If even a small fraction of Arctic sea floor carbon is released to the atmosphere, we’re fucked.”

- Vox: We’re melting the Arctic and reviving deadly germs.

- Scientific American: “Zombie” Anthrax Goes on a Killing Spree in Siberia--How? An outbreak of anthrax that has killed more than 2,000 reindeer and sickened 13 people in Siberia has been linked to 75-year-old anthrax spores released by melting permafrost.

- Arctic News: Rapid warming of the Arctic are pushing us towards four tipping points: (1) loss of all ice (blue ocean event); (2) latent heat tipping point (Arctic emits more heat than it absorbs) (3) seafloor methane tipping point (4) Terrestrial permafrost tipping point.

- Guardian: Mass melting of Antarctic ice sheet led to three metre sea level rise 120,000 years ago. Cause of rise was ocean warming of less than 2°C.

Soil is vanishing

Desiccated by drought, washed away by flood, burned by fire, poisoned by pesticides, churned up by machines: how little respect we show our Mother Earth. Just a slim layer of topsoil provides most of our nutrition and supports most surface life on earth, yet we treat it with contempt, living as if tomorrow will never come.

- Time: A broken food system is destroying the soil and fuelling health crises as well as conflicts, warns Professor John Crawford of the University of Sydney.

- GIZ Cambodia: Let’s talk about soil. This animated film tells the reality of soil resources around the world, covering the issues of degradation, urbanization, land grabbing and overexploitation.

- Phys.org: Every meal eaten estimated to cost the planet 10 kilos of lost topsoil. “10 kilos of topsoil, 800 litres of water, 1.3 litres of diesel, 0.3g of pesticide and 3.5 kilos of carbon dioxide—that’s what it takes to deliver one meal, for just one person.”

It’s getting hot

Isn’t it supposed to be global “warming”? Then how come it’s so hot! While writing this article, it peaked at 46°C in western Sydney where I live. It’s too much.

- Guardian: Climate change to cause humid heatwaves that will kill even healthy people. If warming is not tackled, levels of humid heat that can kill within hours (“wet bulb temperature”) will affect millions across south Asia within decades.

- Proceedings of the National Academy of Science U.S.A.: Peak heat stress, quantified by the wet-bulb temperature, will kill humans and other mammals, as dissipation of metabolic heat becomes impossible.

- Science Advances: Deadly heat waves projected in the densely populated agricultural regions of South Asia. “Climate change, without mitigation, presents a serious and unique risk in South Asia, a region inhabited by about one-fifth of the global human population, due to an unprecedented combination of severe natural hazard and acute vulnerability.”

- Colombia U: Killer heat waves will become increasingly prevalent in many regions as climate warms.

- Nature Climate Change via Time: Ocean Acidification Will Make Climate Change Worse.

- NRK: Global warming has begun to make Norway warmer and wetter.

- Guardian: On a planet 4°C hotter, all we can prepare for is extinction.

- XKCD: A timeline of earth’s average temperature since the last ice age glaciation. When people say “the climate has changed before” these are the kinds of changes they’re talking about.

Effects on humanity

It is easy to get hold of information about the material effects of our collapsing ecosystems. But I am a monk, and I wonder about our humanity. What does it mean for us as human beings, to realize the true enormity of what we have done? Will we ever be ready to take responsibility for our choices, our greed and complacency? Who are we that would do such a thing?

Food: hunger on the rise again

There are few sights more heartbreaking than the image of a starving human being. Living in a developed nation knowing only abundance, it is in starvation that we see the true meaning of inequality. It’s such a fine line between abundance and despair. My home state of Western Australia grows 50% of Australia’s wheat in the marginal and arid wheatbelt east of the Darling Range, where even a small fluctuation in the weather can spell disaster for the farmers.

- WA Dept. of Primary Industries: Climate projections for Western Australia. “Average annual temperature will increase by 1.1–2.7°C in a medium-emission scenario, and 2.6–5.1°C in a high-emission scenario by the end of the century.” Rainfall and available water decrease, while evaporation and fires increase.

- FAO: The number of undernourished people in the world has been on the rise since 2015, with more than 820 million people in the world still hungry today.

- Minnesota U: Climate change is already affecting crop yields and reducing global food supplies.

- The Globe and Mail: Extreme weather leaves 45 million in Southern Africa facing severe food shortages—and the link to climate change is increasingly clear.

- Oxfam: Drought in East Africa. “If the rains do not come, none of us will survive.”

- Al Jazeera: Deadly drought in southern Africa leaves millions hungry.

- BBC: Locust swarm: UN warns of food crisis in Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania and Somalia.

- The Nation: Climate Change Is Here—and It Looks Like Starvation. But don’t expect to hear about it on the nightly news. “We, living humans of the planet Earth, can no longer afford not to see one another, and not to listen to each other’s cries, shouts, demands.”

- Phys.org: Newly identified jet-stream pattern could imperil global food supplies. “… simultaneous crop-damaging heat waves in widely separated breadbasket regions—a previously unquantified threat to global food production … the heat extremes linked to the patterns will become more severe, because the atmosphere as a whole is heating … many consensus scientific statements, including those from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change have proved to be underestimations of how fast and far the effects of global warming might move.”

- Anglia Ruskin University & British Foreign Office: Food shock study highlights the unsustainability of our current course. “based on plausible climate trends, and a total failure to change course, [by 2040] the global food supply system would face catastrophic losses, and an unprecedented epidemic of food riots. In this scenario, global society essentially collapses as food production falls permanently short of consumption.”

Health and well-being: no-one is immune

The wealthy can afford to buy face masks and air purifiers, to seek medical aid and treatment when they need it. All these things are denied to the poor, not to speak of the homeless, relentlessly exposed to the elements. Yet even the richest, at the end of the day, must breathe the same air as the rest of us. We have taken so much from our children: clean water, pure air, benign sun. Women today are struggling with the impossible choice of whether to have children in a world facing collapse. Yet perhaps the worst thing we have taken from our children is their choice. If they survive, what will they be thinking when it comes time for them to have have their own children?

- Job One: The 20 worst consequences for humanity.

- Washington Post: “On land, Australia’s rising heat is ‘apocalyptic.’ In the ocean, it’s worse”.

- The Lancet: 2019 report, by over 100 experts on the health impact of global heating, says “The life of every child born today will be profoundly affected by climate change. Without accelerated intervention, this new era will come to define the health of people at every stage of their lives.”

- Wired: Article on the Lancet report, with graphs.

- Independent: Climate change linked to suicides of 59,000 farmers in India.

- Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA: Crop-damaging temperatures increase suicide rates in India. “Fluctuations in climate, particularly temperature, significantly influence suicide rates. For temperatures above 20°C, a 1°C increase in a single day’s temperature causes ∼70 suicides, on average. This effect occurs only during India’s agricultural growing season, when heat also lowers crop yields.”

- Guardian: ‘Overwhelming and terrifying’: the rise of climate anxiety. Experts concerned young people’s mental health particularly hit by reality of the climate crisis.

- UN expert: Climate change will have the greatest impact on those living in poverty, but also threatens democracy and human rights. “While people in poverty are responsible for just a fraction of global emissions, they will bear the brunt of climate change, and have the least capacity to protect themselves. We risk a ‘climate apartheid’ scenario where the wealthy pay to escape overheating, hunger, and conflict while the rest of the world is left to suffer.”

- Scientific American: U.S. Is Unprepared for the Health Challenges of Climate Change, Experts Warn.

- Climate Reality Project: Health and heatwaves.

- Eartharxiv.org: Neuroscience research—Fossil fuel combustion is driving indoor CO₂ toward levels harmful to human cognition.

- Youtube: Experiments show cognitive impairment from stale air.

- Vice: “We Fear for Our Children.” Alaska Natives Speak out in Climate Change Report. NOAA’s annual report on the devastating effects of climate change in the Arctic is highlighting the unsettling changes to the lives of the people who live there.

- Guardian: If I have no hope for the planet, why am I so determined to have this baby? I wonder if my child will ever have the innocence I had two months ago, of not having to think about whether the air will kill you. “The sky over our Canberra home is tinged orange, the air is thick and sticks in the back of your throat in such a way that no coughing seems to dislodge the sensation. The whole country is suffocating. We haven’t seen the sky in a month.”

- Guardian: Being pregnant in a climate emergency was an existential challenge. Miscarriage has brought a new grief. The bushfires turned an abstract fear into a concrete reality. Having lived on the frontlines of climate collapse, I’m not sure I will choose to get pregnant again. “Sitting in my bedroom in the orange semi-light at midday I looked at the murky sight outside my window and wondered ‘What have I done?’”

A decaying ecosystem drives war and conflict

Progressives and activists tend to assume the best of people. We like to think that as things get worse, people will wake up and make positive changes. And sure, that’s not all wrong. But it’s not all right, either. It’s also true that when the pressure is on, people close ranks, arm themselves, and see others less as friends and more as threats. We are going see increasingly extreme acts of violence, both state-sanctioned and personal, as our faith in civilized institutions fades away.

- Times of India: Water crisis brews between India and Pakistan as rivers run dry.

- Pentagon Fears Confirmed: Climate Change Leads to More Wars and Refugees.

- Iowa State U: Climate change increases potential for conflict and violence.

- Davos World Economic Forum: Climate change is greatest risk world faces.

- Scientific American: Once Again, Climate Change Cited as Trigger for Conflict. “The national security establishment needs to prepare for a series of global crises sparked by climate change, a group of experts wrote in a report released today.”

People forced from their homes with nowhere to go

When I was in Vienna several years ago, it so happened that a former prime minister of Australia was visiting Europe, touting Australia’s vicious and criminal treatment of asylum seekers as an example for the world. What was interesting for me to see was the support he got from the Nazis. Not the “internet troll” kind of Nazi, but your actual jackboot-wearing, Mein Kampf-reading, holocaust-enthusiast Nazis. They thought Australia’s asylum seeker policies are great. I take this as a warning: how depraved the acts of a supposedly civilized nation may become in the face of a minuscule trickle of poor, brown people on boats.

I believe that the movement of people will be the tip of the spear. The numbers will go from the thousands to the millions, and from the millions to the hundreds of millions. And no-one has an answer to the one basic question: where will they all go?

The political right has been telling us for years that the movement of people is an imminent threat to our nation and our way of life. You can’t have a nation if you can’t defend your borders, they say. They’re lying, of course. The historical movement of people into developed countries poses no such threat, and indeed is strongly associated with economic and cultural growth.

Yet there is a point at which the lie becomes the truth. The water runs dry, the cities break down, and a nation cannot survive. That day may be mere decades away. As compassionate progressives, our impulse is to embrace the lost and the disadvantaged in the belief that helping those in need is both moral and practical. But we are yet to face our day of reckoning. What are we going to do when the dark fantasies of the right become our reality? What are we going to do when it is time to open the doors of our homes? And what karma will we carry when our turn comes to seek shelter in the home of another?

- Phys.org: Warmer climate leads to current trends of social unrest and mass migration: study.

- New York Times via Ecowatch: Seven million people were displaced from their homes due to extreme weather events in the first half of 2019.

- Oxfam: Climate fuelled disasters number one driver of internal displacement globally forcing more than 20 million people a year from their homes.

- World Bank: 143 million people will be displaced by 2050 due to climate change.

- Vice: Despite the vast numbers who will be displaced by climate change, there is no legal recognition of climate refugees, and no plan.

- DW Documentary: Fleeing climate change—the real environmental disaster (German public broadcaster).

- NY Times via non-paywalled source: Central American Farmers Head to the U.S., Fleeing Climate Change. “Gradually rising temperatures, more extreme weather events and increasingly unpredictable patterns—like rain not falling when it should, or pouring when it shouldn’t—have disrupted growing cycles and promoted the relentless spread of pests. Guatemalans harvesting coffee in Honduras, where there is a shortage of workers. The obstacles have cut crop production or wiped out entire harvests, leaving already poor families destitute.”

How did it get so bad?

It’s not just a failure of public policy or private lifestyle. It’s a failure of morality. We have become adept at deflecting responsibility. Greg Hunt, the former Australian Minister for the Environment and architect of our failed “Direct Action” policy, justified his approach by arguing that if we implemented a carbon tax, China would never follow suit. Well, I’m not sure how closely China has modeled its environment policy after the literal world’s worst, but my guess is, not much.

We’ve become used to such statements. The rich and the powerful, when in the mood to admit that climate change is real, say there’s nothing they can do, as we only make such a small contribution. This line has become so normal it’s easy to forget that it is the very definition of immorality. Our moral life is based on the Golden Rule: do unto others as you would have them do unto you. It assumes that our good actions will be mirrored by those we affect. The inaction urged by the right is the exact opposite: do unto others and make sure they never, ever, ever do unto you.

Climate change disproportionately impacts the poor and the disadvantaged. For this reason, activists have made the case that action is an urgent moral necessity. I have come to believe that this strategy was a mistake. The suffering of the poor is not a bug, it’s a feature. The rich built the system, and they built it to externalize the costs of wealth and power so that someone else has to pay. Preferably someone poor, brown, and over there.

There was a memorable article in my local paper, the West Australian, back in the 80s. For the first time, a big American motivational speaker came to little old Perth, and inspired thousands with his message of wealth and ambition. And the last part, he urged, at the end, when you have your big house and all the things you want, you need to do one more thing. Get in your new Mercedes and drive back to the poor suburb you came from. Drive slowly down the streets, and know to yourself, “I made it, and you didn’t.”

Consider how economics works. Purchasing power is relative, so a “dollar” means nothing but a conventional power to purchase things. Let’s say we have a rich man with $100 and a poor woman with $1. The rich man has 100 times the purchasing power of the poor woman. How is the rich man to get richer? He can double his purchasing power by earning another $100. But that’s hard! You know what’s easy? Taking 50c from a poor woman. Now the rich man has $100.50, and the poor woman has just 50c. The rich man has doubled his purchasing power, and is exactly as well off as if he’d made $100 himself. What a win! Of course, this is an unrealistic scenario. In reality, the richest have not $100, but over $100,000,000,000, while millions of the poor would think themselves lucky to have a whole dollar.

It’s really hard to imagine what that kind of money means, but let’s try. For most people, the most significant financial investment they make is in a home, if they are lucky enough to be able to afford one. In a wealthy city like Sydney, the median house price is around $1,000,000, and normally it takes decades of hard work to pay off the loans. Someone who can actually own their house outright is considered fairly well-off. It’s a bit different for the super-rich. Assuming a modest 20% return on their capital, one of the world’s richest men could buy a house in Sydney every twenty minutes for a year, and still end up richer than they started.

It’s not just that the rich are greedy. It’s that wealth only has meaning when someone else is poor. If everyone was a billionaire, money would be worthless. And having a beachfront mansion is great, but how can you really enjoy it if the hoi polloi just waltz on in? Inequality is not an accidental byproduct of wealth, it is what creates wealth.

When faced with the suffering of the poor and the powerless, do we really believe the excuses of the rich, that this as a regrettable but unavoidable fact of the world as it must be? Or is this, rather, the world that they have built for themselves because they wanted it that way? Is it possible that the suffering of others is, in fact, the point?

The End of the World or the end of the month?

I live by choice in a working-class neighborhood among hard-working people who happen to be mostly immigrants. Haul a box of tomatoes, dig a trench, serve a roti. As a monk I have the privilege to be supported by equally hard-working donors, affording me the time to practice, to study, to write, and to teach. I get to stand aside and watch as they get on with their lives. I know that they all just want to be happy, to make money, to start a family and enjoy life. Nothing wrong with that. But I also know that none of that will be possible once the climate collapse starts to bite.

Even after our apocalyptic summer of fire, nothing much has changed. There’s little action on the streets and no revolution in the air. People have a way of setting aside the long game to focus on the present. I don’t know, maybe they’ve got it right.

- NYT: Ordinary people say Macron’s speechifying about the fate of the planet overlooks the month-to-month struggle of their lives. “He’s talking to us about the ‘ecological transition.’ This is a politician who is floating in outer space.”

- Pew Research: 2019 US survey: Climate Change’ ranks 17th out of 18 top concerns for Americans.

- Lowy Institute: 2019 survey: 61% of Australians say global warming is a serious and pressing problem [and] we should begin taking steps now even if this involves significant costs. However, in 2006 68% of Australians said the same thing and no substantive policy eventuated.

- IPSOS via Sydney Morning Herald: Feb 2020 survey: No huge spike in climate alarm after bushfires. “Few of the indicators, measured almost every year for a decade, showed a significant shift after the summer bushfires and the results showed skepticism about the science actually rose compared with the last survey two years earlier … many of the responses were in line with previous surveys and did not show a spike that could be attributed to the bushfires over summer … voters said they wanted action on climate change but were not sure what this should be. They rejected the idea of paying more for electrical power or petrol, or more tax generally.”

- Buzzfeed News: The Hidden Environmental Cost of Amazon Prime’s Free, Fast Shipping. Expedited shipping means your packages may not be as consolidated as they could be, leading to more cars and trucks required to deliver them, and an increase in packaging waste, which researchers have found is adding more congestion to our cities, pollutants to our air, and cardboard to our landfills.

- Vox: Wealthier people produce more carbon pollution—even the “green” ones. Good environmental intentions are swamped by the effects of money. “Rich people emit more carbon, even when they recycle and buy canvas tote bags full of organic veggies.”

Governments in denial: public servants serve the corporations

Growing up in Australia, it’s traditional to, on the one hand, laugh about how all politicians are liars and scumbags, while at the same time be proud of our democracy. That’s changing. The sense I get today is an almost total collapse of faith in government and the very idea of public service. And no wonder. Ten years ago Kevin Rudd, our then Prime Minister, proclaimed that climate change was “the great moral challenge of our generation”. He then proceeded to fail that challenge, massively and systematically. The Australian government has been particularly terrible, but few are the governments around the world who have really taken change seriously. We let our politics be bought by the fossil fuel industry, and they bargained away our future for the sake of a few miserable coins.

- IMF: Global Fossil Fuel Subsidies Remain Large. $4.7 trillion (6.3 percent of global GDP) in 2015 and projected at $5.2 trillion (6.5 percent of GDP) in 2017. The largest subsidizers in 2015 were China ($1.4 trillion), United States ($649 billion), Russia ($551 billion), European Union ($289 billion), and India ($209 billion).

- Vox: “Climate change” and “global warming” are disappearing from U.S. government websites. The deletions follow a pattern of policy changes on climate change under the Trump administration.

- Politico: “I’m standing right here in the middle of climate change.” How USDA is failing farmers. The $144 billion Agriculture Department spends less than 1 percent of its budget helping farmers adapt to increasingly extreme weather.

- Guardian: EU accused of climate crisis hypocrisy after backing 32 gas projects.

- Guardian: Should fossil fuels pay for Australia's new bushfire reality? It is the industry most responsible. It is unconscionable that the taxpayer funds fossil fuels to the tune of $1,728 per person per year.

- Greepeace: Dirty Power: Big Coal’s network of influence over the Coalition Government.

- Guardian: Fossil-fuel industry doubles donations to major parties in four years, report shows. The coal, oil and gas industry gave $1.9m in 2018-19. “Both major parties are dependent on donations from the fossil-fuel lobby. Not only this, but our major parties and their fundraising entities are responsible for a large sum of dark money in our system. With poor requirements for reporting donations, there is little transparency to hold donors and parties to account.”

- Sky News: Australia PM Scott Morrison denies climate change link to bushfires.

- The Australian: What the frack: PM gas plan “new dark age”. In the midst of Australia’s bushfire crisis, PM Scott Morrison announced $2 billion additional fossil fuel subsidy. Bruce Robertson from the Institute of Energy Economics and Finance Analysis says this won’t do what the government is promising—reduce prices or emissions. “Producing more polluting fuels does not lower emissions.” Clean Energy Council analysis shows investment in large-scale renewable energy projects has plummeted from 51 projects worth $10.7 billion in 2018 down to 28 projects worth $4.5 billion last year.

- Common Dreams: “Everything is Burning”: Australian Inferno Continues, Choking Off Access to Cities Across Country.

- Patriot Act on Netflix: How the fossil fuel industry and government, through its goal of “energy dominance,” are pushing for greater oil production. Trump official: “Demonization of CO₂ is just like the demonization of the poor Jews under Hitler.”

- New Republic: Bureau of Land Management Director William Perry Pendley believes the oil and gas industry should be allowed to plunder the country’s natural resources.

- Guardian: Vehicles are now America's biggest CO2 source but EPA is tearing up regulations. Mary Nichols, chair of the California Air Resources Board and a former EPA assistant administrator: “I’ve not seen any evidence that this administration knows anything about the auto industry, they just seem to be against anything the Obama administration did. Vehicle emissions are going up, so clearly not enough is being done on that front. The Trump administration is halting further progress at a critical point when we really need to get a grip on this problem.”

- Guardian: Greenpeace exposes sceptics hired to cast doubt on climate science. Sting operation uncovers two prominent climate sceptics available for hire by the hour to write reports on the benefits of rising CO₂ levels and coal.

- Skeptical Science: Index of climate liars.

- Toronto City News: Ford government spending $231M to cancel renewable energy projects.

- Patriot Act on Netflix: The Two Sides of Canada. Interview with Justin Trudeau.

- NY Times: Smothered by Smog, Polish Cities Rank Among Europe’s Dirtiest. Burning coal is a part of daily life in Poland. As a result the country has some of the most polluted air in the European Union, and 33 of its 50 dirtiest cities.

- Air Quality News: Poland power plant burns one tonne of coal every second.

- The Conversation: COP24 in coal country: why Poland is Europe’s climate denial capital.

- Huffpost: The Brutal Reality Of Being The World’s ‘Best’ Recycler. “Most plastic is incinerated in Germany or shipped abroad to poorer countries, where it’s sometimes dumped or burned illegally.”

- The New Republic: Far-Right Climate Denial Is Growing in Europe.

The heinous lies of the oil companies

What I don’t understand, seriously, is how they get away with it. How can it possibly be legal for companies to just lie and lie and lie about matters of the utmost importance?

- Australian Broadcasting Commission: Omnicide: Who is responsible for the gravest of all crimes? “During these first days of the third decade of the twenty-first century, as we watch humans, animals, trees, insects, fungi, ecosystems, forests, rivers (and on and on) being killed, we find ourselves without a word to name what is happening. True, in recent years, environmentalists have coined the term ecocide, the killing of ecosystems—but this is something more. This is the killing of everything. Omnicide.”

- U.S. Energy Information Administration: The United States is now the largest global crude oil producer.

- U.S. Energy Information Administration: Oil and gas extraction continue to rise in the U.S.

- Dallas News: Permian Basin (Texas, New Mexico) could double oil production by 2023.

- Nature Energy via Stockholm Environment Institute: U.S. oil and gas subsidies could increase production by 17 billion barrels. Nearly half of discovered U.S. oil is dependent on subsidies.

- Global Witness: 61% of the world’s new oil and gas production over the next decade is set to come from the United States.

- Quartz: It took Saudi Aramco just nine months to make $68 billion.

- American Petroleum Institute: In 1980, an accurate forecast of climate change was made by the American oil industry, predicting global catastrophe by mid-21st century.

- Inside Climate News: Exxon: The Road Not Taken. Exxon was warned of climate crisis in 1977, which was supported by their own science, and chose to systematically undermine science for their own profits.

- Scientific American: Exxon Knew about Climate Change almost 40 years ago. A new investigation shows the oil company understood the science before it became a public issue and spent millions to promote misinformation.

- The Intercept: Imperial Oil, Canada’s Exxon Subsidiary, Ignored Its Own Climate Change Research for Decades, Archive Shows.

- Guardian: Exxon has misled Americans on climate change for decades. “Exxon’s own scientists warned their managers 40 years ago of “potentially catastrophic events”. Yet rather than alerting the public or taking action, these companies have spent the past few decades pouring millions of dollars into disinformation campaigns designed to delay action. All the while, the science is clear that climate-catalyzed damages have worsened, storms have intensified, and droughts and heatwaves have become more frequent and severe, while forests have been damaged and wildfires have burned through the country.”

- Bloomberg: As the world strives to wean itself off fossil fuels, oil companies have been turning to plastic as the key to their future.

- Yale: The Plastics Pipeline: A Surge of New Production Is on the Way. A world awash in plastic will soon see even more, as a host of new petrochemical plants—their ethane feedstock supplied by the fracking boom—come online. Major oil companies, facing the prospect of reduced demand for their fuels, are ramping up their plastics output.

- Independent: BP and Shell planning for catastrophic 5°C global warming despite publicly backing Paris climate agreement.

- Guardian: Oil and gas firms “have had far worse climate impact than thought”. Human fossil methane emissions have been underestimated by up to 40%.

- Guardian: Top investment banks provide $700bn to expand fossil fuel industry since Paris climate pact.

- Independent: Nearly 94% of Shell shareholders reject emissions reduction target in line with Paris climate agreement.

- Guardian: Top oil firms spending $200 million/year lobbying to block climate change policies.

- Guardian: Revealed: quarter of all tweets about climate crisis produced by bots. “A substantial impact of mechanized bots in amplifying denialist messages about climate change, including support for Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris agreement.”

The rich did this and they will leave us to die

While their workers struggle day-to-day to pay the bills, the rich have plenty of time to contemplate the big picture. Sometimes they decide to help, so we see the “good billionaires” make splashy public displays of their charity, as if we are supposed to forget that they got rich by crushing competition, exploiting workers, and dodging taxes. Yes, I’m looking at you, Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos.

What the rich keep hidden, for the most part, are their escape plans. When they have ruined the world they aim to live on as immortal lords of the wasteland.

But how much worse is the lifestyle of the rich, really? Let’s do some math! The top 1% emit as much carbon as the bottom 50%. According to Picketty et al. the global 1% emit about 200 tonnes of greenhouse gases annually. That’s a lot! Some studies have produced a lower figure, while others are higher. Let’s take Picketty’s figure. The “carbon budget” to stay under 2°C global warming sits currently at 1,000,000,000,000 tonnes. At current rates it will be used up in 25 years. If everyone emitted as much CO₂ as much as the 1%, we’d reach that target in 8 months. If everyone emitted as much as Bill Gates—over 10,000 times as much as a “normal” person—that 1,600 tonnes per person would slurp up the budget in less than a month. 2°C heating is a lot though. If we wanted to keep heating under a more sane (but still bad) 1.5°C, 8 billion Bill Gates would gobble the world’s carbon budget in a week.

Forgive me if I am skeptical that these people are going to save the world.